Born in 1870s Brooklyn and classified as legally blind for most of his life, Charles R. Knight was probably one of the least likely candidates for becoming a wildlife artist. Nevertheless, with an innate love for animals and a persistence at his work - mixed with a healthy dose of serendipity - Knight would become world-reknown, and esteemed peers in his field, including Jean-Léon Gérôme and Emmanuel Frémiet, would come to declare Knight's drawings of animals, birds, and reptiles, "the most perfect they had ever seen."¹

Though it may seem unlikely now, late 19th century metropolitan New York was a place of many opportunities for a child in love with animals. Nationally, it was a period dedicated to animal discovery: Charles Darwin had only recently published his book Descent of Man, the "Bone Wars" between paleontologists Edward Cope and Othniel Marsh were raging in the American West, and conservationists like Theodore Roosevelt were raising concerns that certain species of wildlife were facing extinction if steps to protect them were not to be taken. Locally, these activities bolstered museums, such as the American Museum of Natural History, which filled its halls with dinosaur skeletons and taxidermic animals from around the world; and fostered zoos, such as the Bronx Zoological Park, which sought to inspire visitors with an active appreciation of nature and wildlife. If animals were a ripe topic, then New York City, with its intellectuals, universities, philanthropic organizations, and media outlets, was the center of the garden.

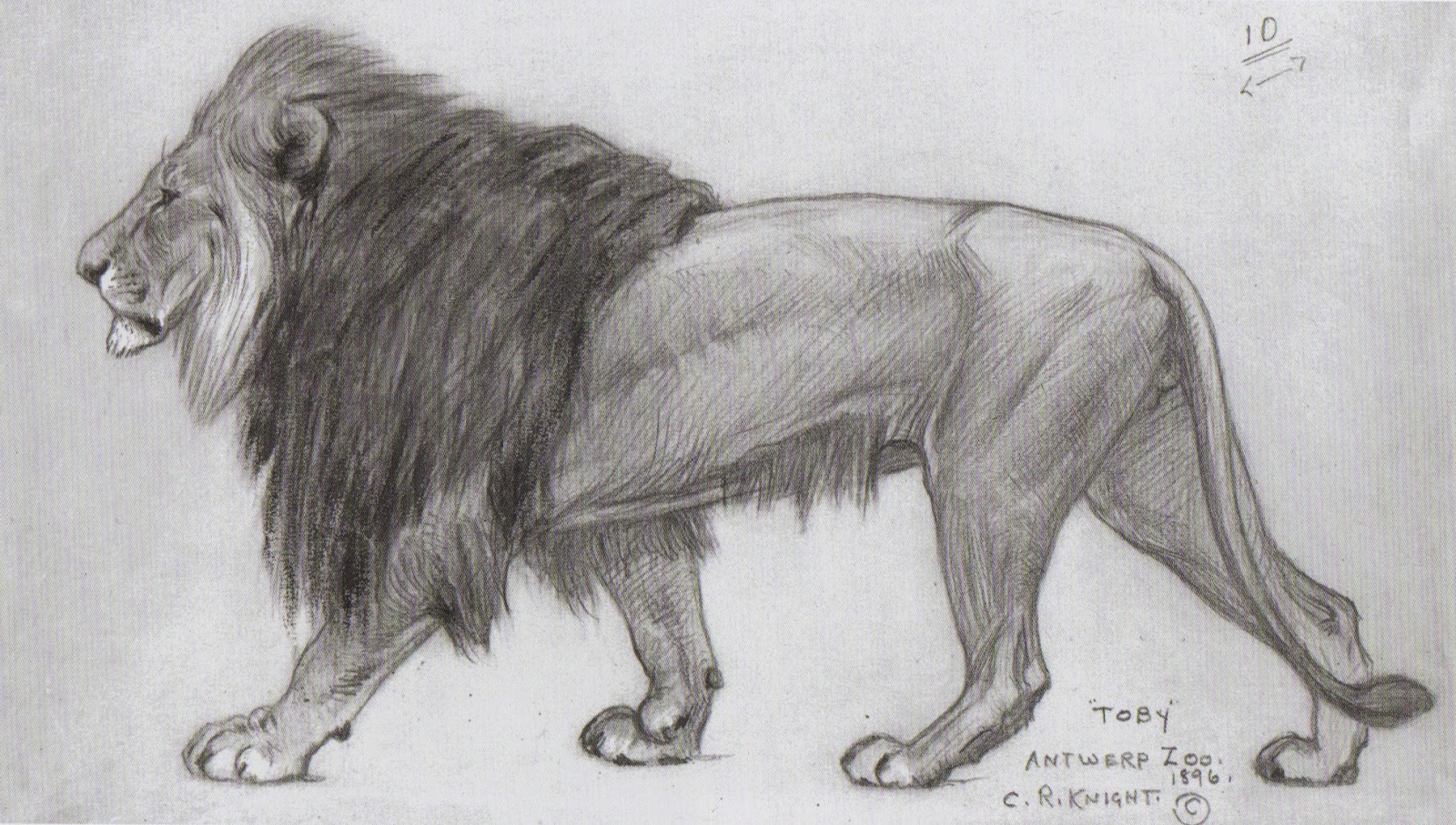

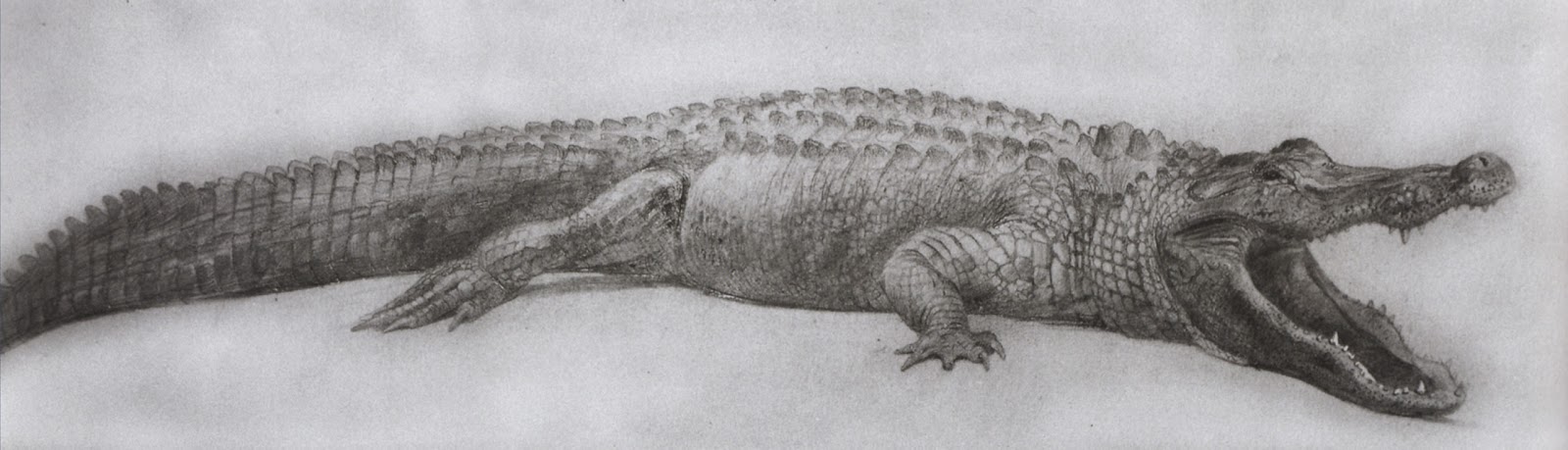

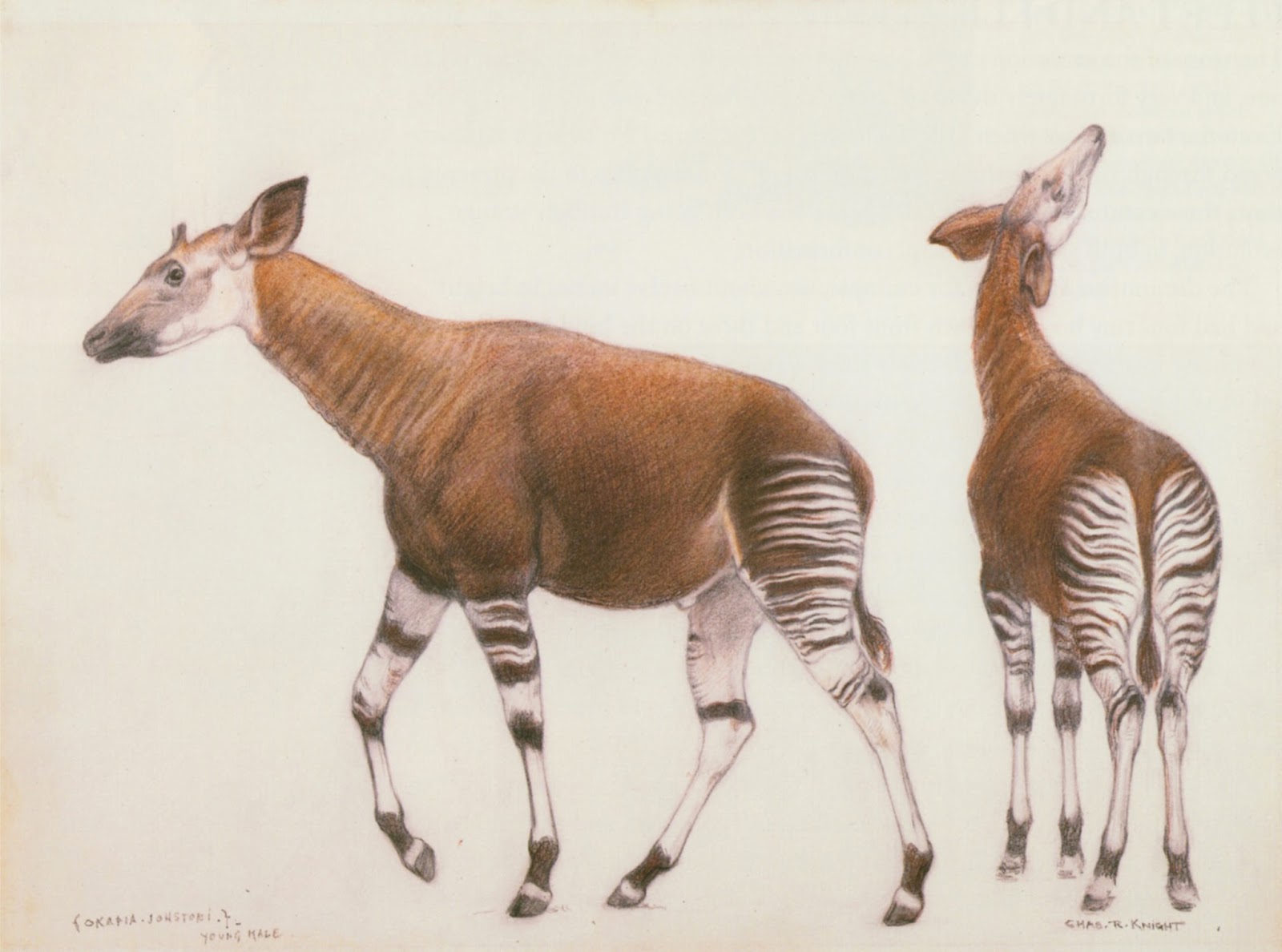

Knight, who fell in love with animals through the illustrations he saw in his family's household dictionary, was fortunate that his father indulged the boy in his interests. Frequently, Knight and his father would travel into Manhattan and attend the Central Park Zoo and the American Museum of Natural History, which Knight described as more or less satisfying his "juvenile yearnings," while at the same time gradually training his eyes to observe with ever-increasing accuracy just what shapes and figures constituted the animal life in the world about himself.² But though these institutions were open to the public, Knight's visits, particularly those to the Museum of Natural History, were far different from the experiences of the ordinary museum-goer. The young Knight, as the child of an employee of J.P. Morgan (Knight's father was Morgan's private secretary, and Morgan was the treasurer of the museum), had access to the museum on Sundays, when it was closed to the public, and he had free roam backstairs where he could watch the exhibition builders and taxidermists at work. It was an intense immersion which likely gave the young man knowledge far beyond his seniors already drawing wildlife.

As a teen, he attended the Metropolitan Museum of Art School, and also the School of Visual Arts, both in Manhattan, and by age sixteen, he had left home and was earning his living as an artist. He began working for a stained glass studio where he was regularly assigned to to design animal panels, and his illustrations of animals began appearing in all of the popular magazines of the day. But it was one particular chance assignment when he was 20 which would set him apart, and set the course for his artistic output for the reminder of his career.

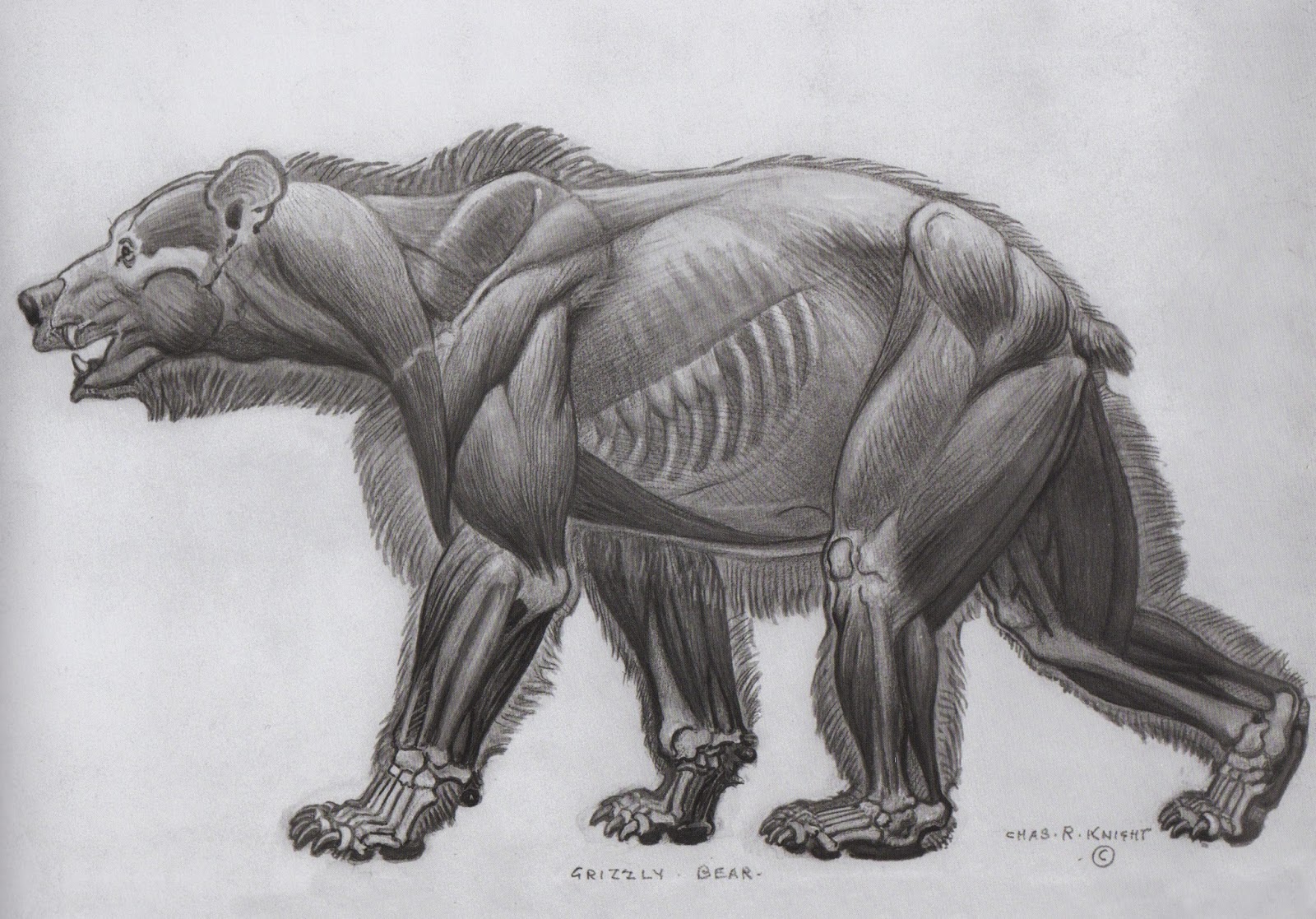

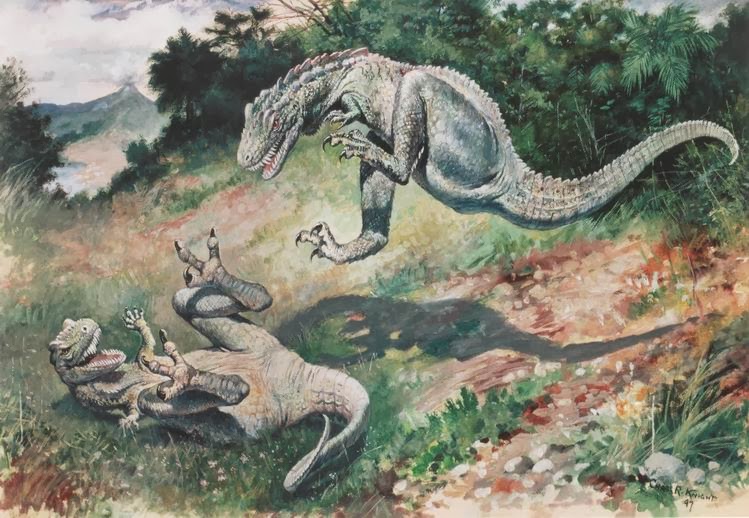

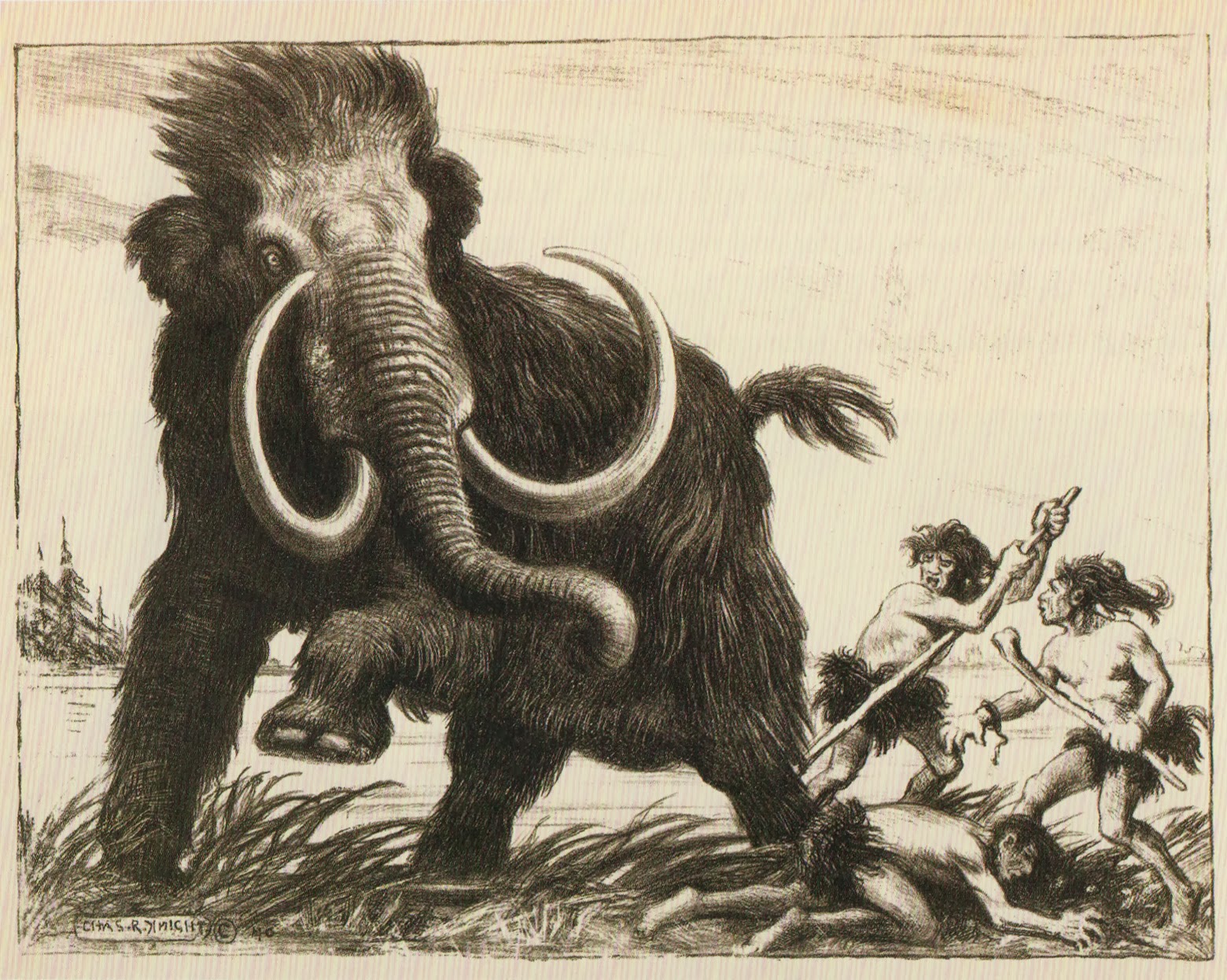

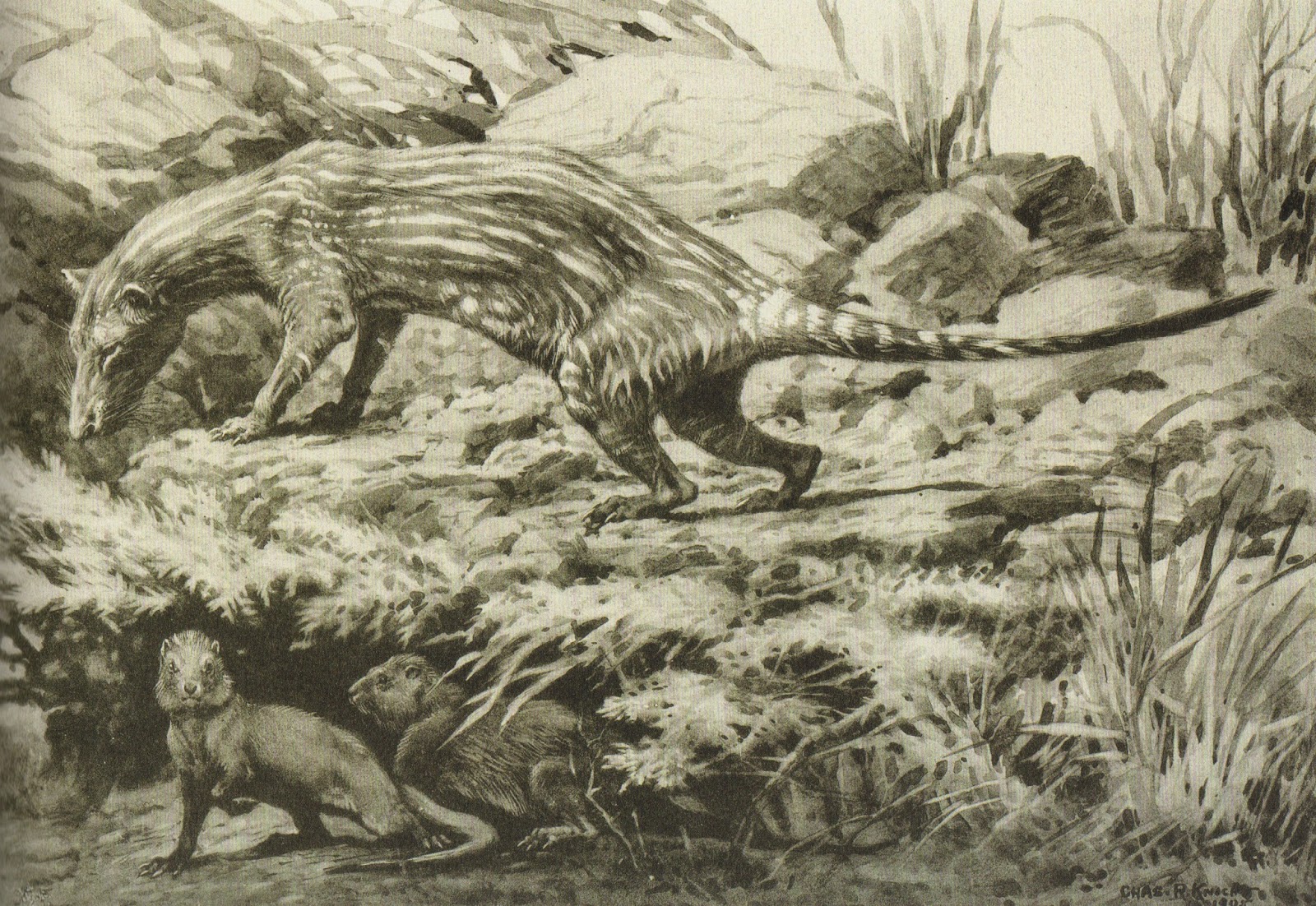

In 1894, during one of his many visits to the the Museum of Natural History, a friend in the taxidermy studio named John Rowley mentioned to Knight that there was an in-house project that might be of interest to him. "There was a man named Dr. Wortman here yesterday, from upstairs in the Fossil Department," offered Rowley, "and he was looking for someone who might make him a drawing of a pre-historic animal. I said I believed you could do it, so why don't you go up and see him?"³ The result was a black and white watercolor of an Elotherium (also known as Entolodon), an extinct, pig-like creature which died out in the Oligocene period, and the painting was so successful at bringing life to the fossilized remains, that Knight became inseparable from the museum's "restoration" team. It was a major advancement in paleontology, and Knight's re-imagined extinct creatures – in combination with the museum's radical decision to mount their fossils in life-like poses, rather than to present them as they had been found, still imbedded in rock – created a wild surge of interest in pre-historic life.

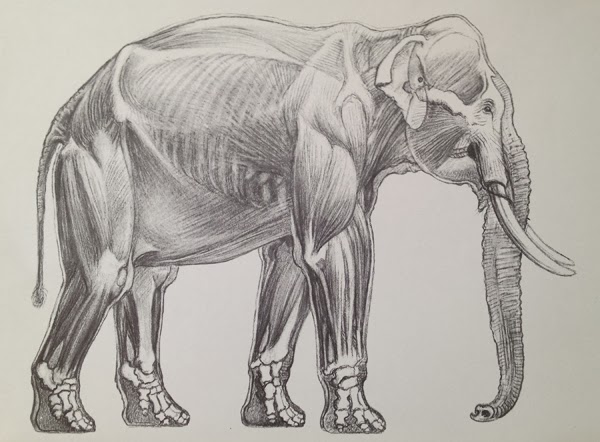

With his advanced knowledge of animal skeletal and muscular systems, and a preternatural understanding of animal psychology gleaned from years of observation, Knight was able to set the standard for re-creating extinct life in drawing, painting, and sculpture. His collaborations with scientists over the next 40 years were groundbreaking, and were responsible for influencing the way the public perceives dinosaurs, from the average T-rex-loving 5-year-old, to the special effects teams working on the multi-million dollar, creature films of today.

By the 1950s, Knight's progressively worsening eyesight had plunged him into a world of darkness. No longer able to produce artwork, he slipped into a deep depression, and in 1953, at the age of 79, he suffered his final heart attack and passed away. And though his name was rather quickly forgotten, his legacy was not; he is without question the father of Paleoart, and his influence is still felt worldwide.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

¹ Milner, Richard, Charles R. Knight: The Artist Who Saw Through Time, (Abrams, New York, 2012), p. 47, in a letter to Henry Fairfield Osborn, President of the American Museum of Natural History, from the American sculptor Eli Harvey dated September 30, 1904.

² Milner, p. 11.

³ Milner, p. 52, from Charles R. Knight: Autobiography of an Artist, (GT Labs, Ann Arbor, 2005).