During his lifetime, wildlife and Paleo- artist Charles Knight wrote several books, mostly on the topic of pre-history. One of his books, however, Animal Anatomy and Psychology for Artists and Laymen (1947) was intended for aspiring wildlife artists. It is filled with his advice on understanding animals, as well as with many of his excellent drawings. Most of the following quotes come from that book, but many can also be found in the recent biography, Charles R. Knight: The Artist Who Saw Through Time by Richard Milner. Milner's book is a short but very interesting read, and offers a wonderful insight into Knight's life; Knight's drawing book, now titled Animal Drawing: Anatomy and Action for Artists is still available for purchase as a Dover Editions reprint, and it is as much an autobiography as a collection of his animal studies.

What made Knight unique among his contemporaries in wildlife art was his emphasis on understanding the "psychology" of animals. Many believed that it was ability to recognize the emotions and motives of animals that allowed him to excel at representing many species of animals, rather than being a specialist, and that this empathy also aided in his ability to render scenes of extinct animals convincingly.

-----------------------------------------------

. . . it is a matter of prime necessity for the artist to examine not only the anatomy but also the mental traits of an animal before he can properly represent a lifelike attitude, in either action or relaxation. The artist must also study the actual appearance of a three-dimensional object with all its diversified planes, light and shade effects, color pattern, and skin embellishments– hair, feathers, scales, etc., as the case may be.

. . . every artist, no matter what his individual proclivities, should study and learn as much as possible of the general as well as the particular phases of his profession in order to do his best in any special line. In other words, sound academic drawing of all objects, be they plaster casts, human figures, animals, or landscapes, is a prime necessity for all of us. Painting, its color qualities, light and shade, atmosphere, values, and all other things that go with this section of art work, should of course be studied constantly. Composition, an enormously important part of art work, necessarily should occupy much of our attention, and the various mediums best suited for certain types of impression should be understood and experimented with.

We must remember that we are faced with a very difficult but fascinating problem when attempting the study of animal life and that in order to attain even a modicum of perfection we must realize that a tough job lies before us. Without hard work, constant application and study, and a proper reverence for the beauty of created forms, we shall not be able to reach our objective.

For the purpose of the artist, a profound knowledge of the deeper muscular anatomy is not absolutely necessary, though some of us may find pleasure and profit in such a line of research. What we should all like to know, however, is the general structure and proportions of the bony skeleton and the principal overlying sets of muscles that cover it at almost every point and control the actions of the bones themselves. The proposition before us really resolves into four or five divisions in the case of most animals under discussion, of which the following are typical examples.

1. The bony structure– its proportions and characteristic attitudes in different species of animals.

2. The principal muscles and tendons covering this skeleton– their shapes, sizes, and general functions.

3. The actual appearance of a given animal in life– its color, hair disposition, and character– and the effect of the underlying structure on the exterior as a whole.

4. The psychology of the animal– a very important feature, for without accurate knowledge on this point we are unable to visualize properly the creature as a living emotional entity. Each species will naturally exhibit its own particular attributes in this respect.

5. The artistic possibilities of certain animals, some species being wonderful in color, others in form, still others in mere picturesqueness or grotesque qualities.

Animals are solid, three-dimensional, animated beings and must be so regarded by the artist and treated accordingly in his paintings and models.

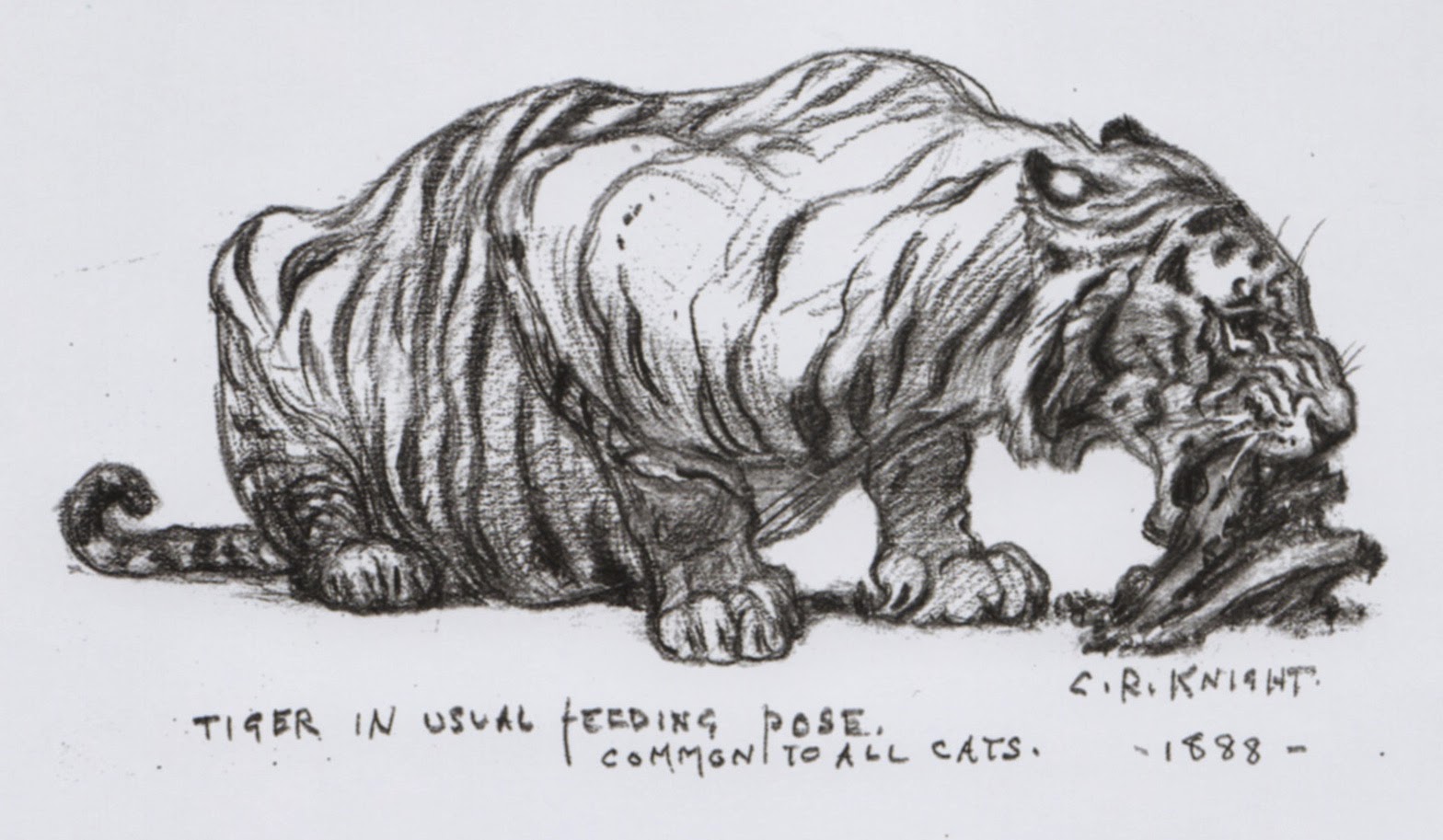

Owing to the protective coloring of most of the cats, both the general form and the muscular anatomy may be very much concealed by the maze of stripes, spots, and irregular markings that constitute a great number of their skin patterns. For this reason it is advisable for a novice to study the lion and the puma, whose most monotone coloring discloses the muscular form to advantage.

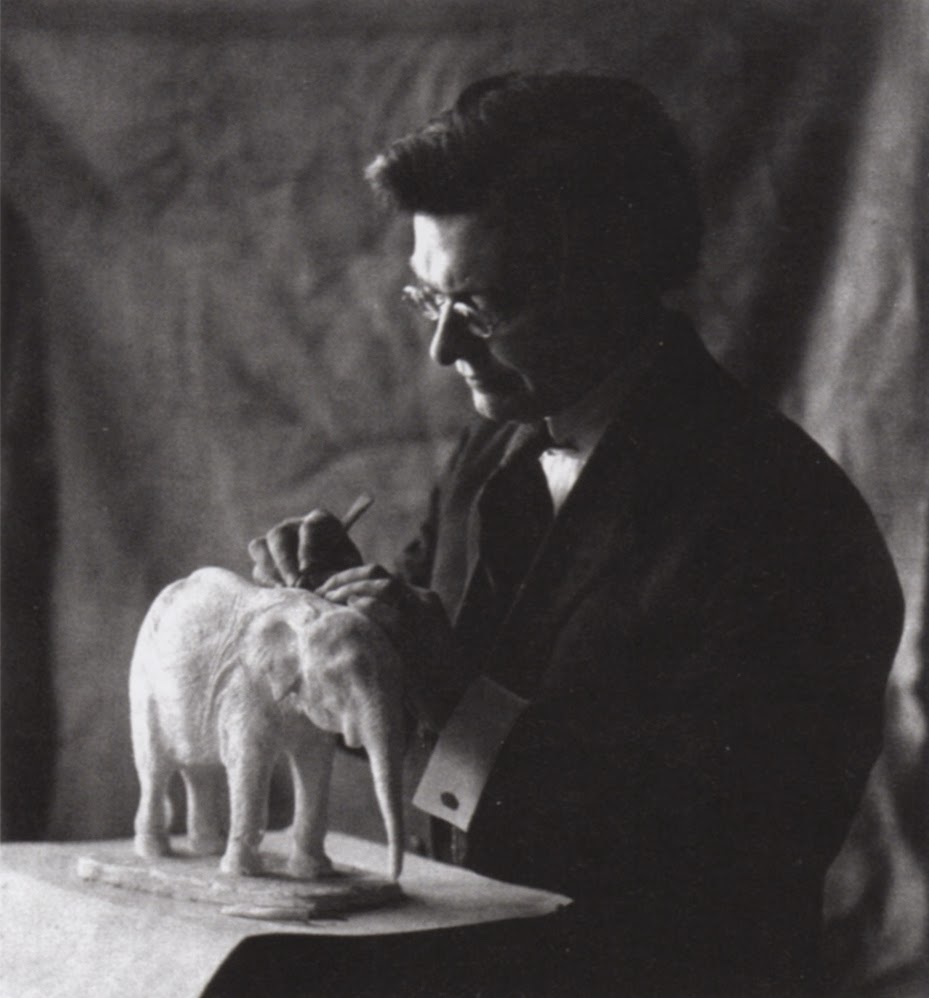

Because of the elephant's bulk the planes of the body are very evident in a strong light but not so noticeable from a near view or in poor illumination. For this reason it is always advisable when possible to look at an elephant in the open and in bright sunlight, when the lights and shadows on the body will be much more evident. Too many attempts fail miserably to represent the creature because the artist knew nothing of these planes; the result can be only a rounded, stuffed-looking production without any true character.

. . . we may reiterate the necessity for a most careful study of comparison of the shoulder region in man and his fellow mammals. We may also stress the fact that the point of juncture of the humerus and shoulder blade is of paramount interest to the student. In man it is more or less fixed in place, whereas in other animals it moves forward and backwards as the creature walks or runs.

Make it a rule to study carefully the species upon which you are to work. . .

Drawing with character (is) simply another name for knowledge of what you are doing.

You should acquaint yourself at least superficially with the psychological traits of the particular type of creature on which you are working.

There will be (and should be) many days when you will make no attempt to draw your model but will merely absorb the various actions and reactions of the different species – how an antelope looks when alarmed or angry, a snarling wolf or fox, or enraged tiger, or the antics of a group of young lions.

. . . it will be of great benefit if you will learn to classify the different types under observation, realizing that all the species of one great race will act in pretty much the same way under similar similar conditions.

It will be well also to read books on the subject of animals in a wild state, their habits and environment and all other data concerning them. Such reading will stimulate and interest you and give you much insight into animals' special modes of existence, all of which will be a help when you come to draw them.

For drawing, nothing that I have ever used can quite compare with the good lead pencil for flexibility, convenience, speed, and durability. Pencil also . . . has the great advantage of being easily removed in case a mistake has been made.

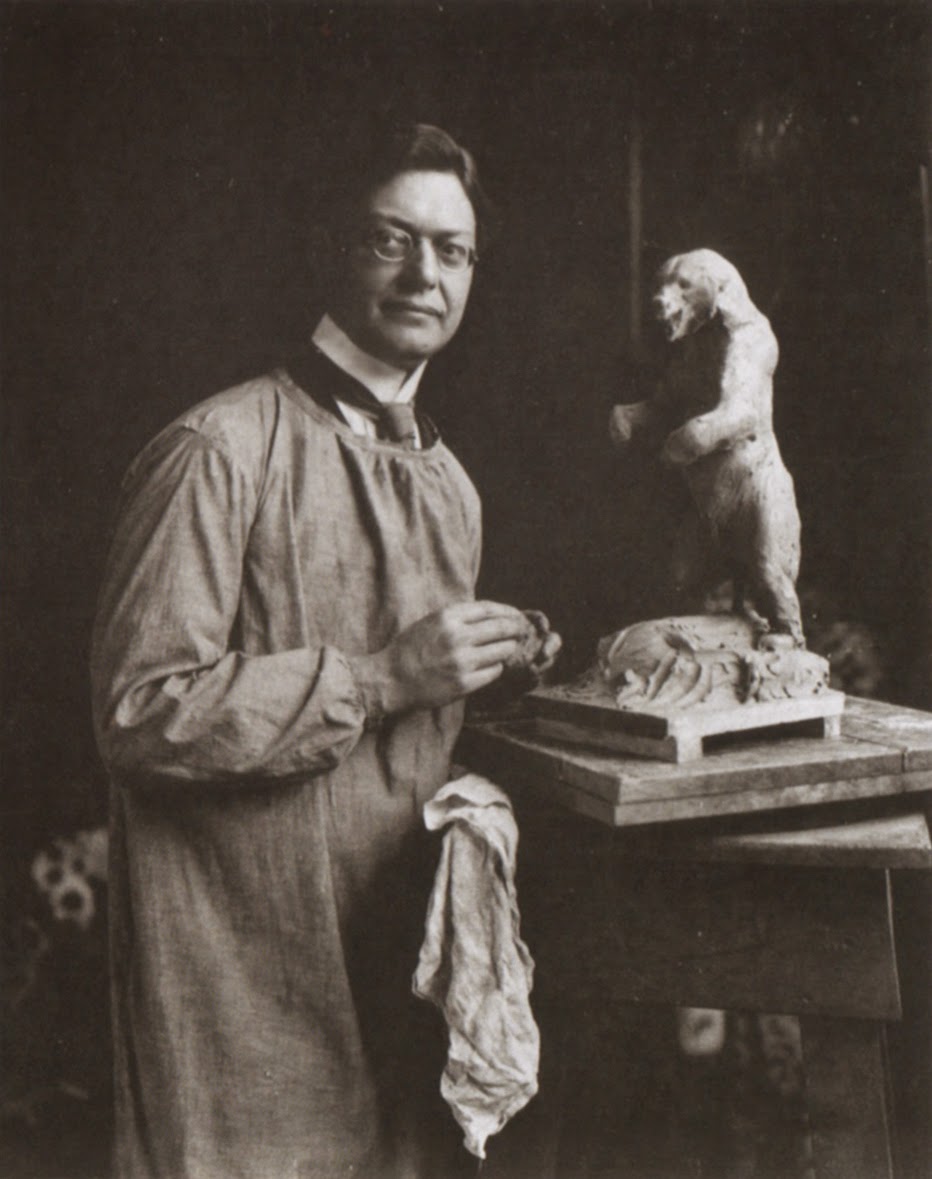

Another little trick that I have found very advantageous is to make at some point in your work a small model either in plastilene or in clay, indicating carefully and completely the construction, silhouette, and principal planes. This is a scheme quite commonly used by animal painters, as it crystalizes the three-dimensional effect. If this model is then placed in the sun, perfectly convincing cast shadows can be secured, shapes very difficult to imagine but that will add greatly to the finished effect of your picture.

Water color either pure or with white (gouache) lends itself readily to many forms of animal painting

Without doubt, when it comes to painting large finished pictures of animals against a background, there is no medium that quite compares with oil.

From a sculptural angle, animals offer some of the very finest opportunities for artistic expression.

. . . anyone drawing in a public place is an absolute lodestone. Most persons are attracted to such a one-man exhibition in a most surprising degree. Almost all of these, you will find, are merely curious and politely interested, but others take advantage of one's helplessness to impress one with the fact that a certain ethical cousin , who "never took a lesson in her life," can "sit right down and draw a perfect portrait of anyone in five minutes." I've always wanted to meet that gifted relative, but without seeing her work I rather imagine I can guess just how much it's worth. It's a dreadful bore, of course, but you must learn to ignore all these little interruptions and try to concentrate on the business at hand, which is, Heaven knows, difficult enough under the best conditions.

Today with the excellent lenses of the modern camera, splendid snapshots of wild animals are easily obtained. Consult but do not copy from these often superb examples of photographic art.

I never make any direct use of photographs, for then I should have to credit the photographer. My work is always strictly original and I use a photograph merely as a reminder.

Remember too that above all it is art we are seeking to experience . . . that our own individualities are being consulted at all times, and that the better artists we strive to become the finer will be our productions in the field of art expression.

. . . drawing is drawing, no matter what the subject, and exactly the same rules of light, shade, contour, perspective, and construction apply equally well in every instance.

[We] work more or less from the inside out to do a really fine painting of an animal and no amount of merely artistic technique in the superficial finish of our production will compensate for a lack of knowledge on this vital point. Both mentally and physically we must to a certain extent "feel" the attitude we wish to portray in order to grasp the coordinated rhythm of the animal's body and mind under a given stimulus of emotion. Lack of knowledge on this important point is what makes so many attempts at animal portrayal rather poor, meaningless accomplishments without truth or interest.

We as artists are not making as much of the unparalleled opportunities for study of animal life that our great zoos and museums afford. Think of how many fine subjects there are for artistic compositions if we would only make use of them. A tiger, for instance, coming out to drink at dusk, the last rays of the sun glinting on the splendid striped coat as the creature stoops to lap the water from some quiet pool. Could anything be finer as a subject for a great painting? Yet we ignore this and hundreds of other equally splendid subjects in our picture exhibitions and confine ourselves to trite and much overdone compositions from which all originality has long since departed.

All artwork should be undertaken as a joy and a pleasure, not as mere drudgery. . . . To explore even a few of these mysteries . . . will surely demonstrate very convincingly the joy of deeper understanding of Nature's story.

Don't let anything happen to my drawings! (Charles R. Knight's last words)