"(William) Orpen draws with just the same accuracy a turnip, a horse, or a complicated arrangement of figures . . . He is a very methodical, business-like Irishman, despising the word 'art,' and having no use for the word 'genius.'" ~ George W. Lambert, one of Australia's most distinguished painters, in an address to his students at the Sydney Art School

There is a story told among members of the Orpen family that says when the artist William was an infant, and still unable to hold drawing instruments in his tiny hands, that he tried to make sketches holding a pencil clasped between his lips. As unlikely as anecdotes like these are, they are charming, and often form the mythology that surrounds an artist's life. Ordinarily, these tales are born in retrospect, after an artist has achieved fame, but in the case of an extremely precocious artist like Orpen, the mythology surrounds the child at an early age and shapes the person into which they grow.

William Newenham Montague Orpen could have probably chosen any profession he wished. He was born November 27th, 1878 to parents Anne, the daughter of Charles Caulfield, Bishop of Nassau, and Arthur, a successful Dublin solicitor. His childhood home, 'Oriel,' with its stables and tennis courts, was large and comfortable, and his family, of which he was the youngest of five children, was never in want. It could have easily been supposed that William would have followed in the footsteps of his father and two of his older brothers, and pursued law, but when he evinced a talent for art at a young age, his mother greatly encouraged him. She, her husband, and the eldest Orpen boy, Richard, were, in fact, all talented amateur artists who had exhibited in Dublin, and Anne wanted at least one of her children to become a professional; as the youngest, William was his mother's last hope for having an artist in the family.

At the tender age of 12, William was enrolled in the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, where he quickly stood out for his hard work. Already possessed of the "Protestant Work Ethic," Orpen put in long days at the school, leaving 'Oriel' each day at 9am, and not returning home until 10:30pm, when he would supper and discuss his work with his mother. The pockets of his coat - or whatever coat he absentmindedly grabbed that day at school - were always stuffed full of his sketches, and his headmaster, James Brennan, upon seeing the young teen set up on a camp stool assiduously drawing from a statue at the National Museum, declared that Orpen would some day be President of the Royal Academy.¹

By the time he reached the prestigious Slade School in London at the age of 17, Orpen was already such an accomplished draughtsman that he was allowed to skip the first year curriculum of cast drawing, and move straight into the life drawing classes. In the classroom, Orpen's fellow-students would gather around his easel to watch him draw, and whatever pencils or papers he was seen using became the de rigueur implements for his classmates, as they hoped the right tools might bring them closer to their idol. And not only did his peers admire his work, so did his professors, who were known to conduct lively bidding behind doors, trying to acquire the young man's classwork. During those years at the Slade, it was truly a one-man show, and that man was Orpen.²

After four years at the Slade, during which time he won nearly every accolade the school had to offer, Orpen decided to embark on his professional career. His initial successes came as a result of showing at the New English Art Club, an alternate venue to the Royal Academy which appealed to younger artists and which was - because of political connections - particularly kind to Slade graduates. Though he did well for the next several years, it was not until 1908 that his career really began to flourish. In that year, seemingly unbeknownst to Orpen, one of his portraits was submitted by a patron to the Royal Academy for exhibition; not only was it accepted, it was given a place of honor in the annual show.³ Orpen's acceptance by the RA (he was made an Associate in 1910, and finally a full member in 1919) opened the artist up to a wider audience of affluent sitters, and within a short period, he was one the most prosperous portrait painters in England.

During the last thirty years of his life, Orpen painted nearly 600 portrait and portrait groups.⁴ He was so busy, that outside his Chelsea studio, chauffeurs leaned against the hoods of the queueing limousines,⁵ and it was not uncommon for a departing client to meet the next sitter while crossing the threshold.⁶ And for each of the four years leading up to his death in 1931, Orpen made no fewer than £45,000 from his painting, an amount equivalent to over $3.3 million per year by modern terms. In his best year, 1929, he made what amounts to 2.7 million British pounds - or over 4 million US dollars.

To accommodate the sheer volume of commissions Orpen was receiving, he enlisted the help of studio assistants. These aides, such as Irishmen Sean Keating and James Sleator, had been exemplary students Orpen discovered while teaching in Dublin, while others, like Englishman Reginald Eves, were Orpen's contemporaries⁷ at the Slade School and were taking on extra work while attempting to establish their own careers. Their duties could range from preparing canvases, to laying in a copy over which Orpen would later work.⁸

Orpen was not adverse to occasionally employing photographs as a labor-saving expedient⁹, but to what extent he made use of the camera is not clear. There is record of Orpen painting animals from photographs, but not people (though it is not inconceivable). He did, however, have definite ideas on capturing a sitter's character, and not just his likeness, which would suggest a distaste for slavishly copying photographs:

The line which separates character from from caricature is very narrow and delicate. It is not a difference that you can measure with a foot-rule . . . It is a quality in the painter's mind that sees what a man is rather than what he looks like. For frequently, if you paint only what you see with your eyes, you will be painting a lie. . . . I have often seen unsympathetic or repellent photographs of a man who turned out charming when you met him. The man had the same face but a different heart, and it is with the heart that the portrait painter is concerned.¹⁰

Orpen also considered it the artist's duty to "organize according to his aesthetic sense the material supplied by the camera," and never allowed the camera to design the pictures for him.¹¹

Much has been made of Orpen's reliance on the square for the compositional arrangement of his portrait paintings, a shape not commonly used in that genre. Typically, Orpen would set his figure in a quite-obvious pyramidal shape by arranging the sitter's elbows on both arms of a chair, or by adjusting the sitter's pose so that their arms were placed akimbo.¹² He would then arrange the curtain-folds of the backdrop in such a way that the diagonals ran from the upper corners to the center of the painting, rather than the customary placement of the drapery running from the upper center to the outside edges.¹³ This arrangement was particularly effective when the seated figure was in profile, and in such a manner, Orpen made use of this design for the length of his career. By one estimate, he painted well-over 100 portraits with this composition, but considering his overall output, this does not translate to a high percentage of his paintings. However, Orpen's popularity among young artists led many followers to adopt the shape, which for a time was quite fashionable.¹⁴

In his early paintings, Orpen was interested in depicting the qualities of natural daylight, and many of his best received works at the beginning of his career were subtle atmospheric studies of ordinary rooms which just happened to contain figures. But as his focus changed almost exclusively to portrait painting, his choices in lighting also changed. By illuminating his sitters from both sides, he eliminated the heavy shadows of his earlier, chiaroscuro-filled images, and this likely pleased his clients who were more interested in clear, unblemished representations of their visage rather than having portions of their face fade off into the backgrounds. This did not mean he abandoned high-contrast images, however, as he frequently would place the well-lit heads of his clients against very dark backgrounds (this formula also likely allowed Orpen to speed up his painting process and thereby his productivity).

Prior to World War I, Orpen employed a restricted palette for his figurative paintings. In 1914, while painting a portrait in Scotland, Orpen shared his colors with Frank Morley Fletcher, then director of the Edinburgh College of Art. According to Fletcher, in his book Colour Control, when he asked Orpen to recommend a palette to the students, Orpen replied that he used only four colors - in addition to Black and White - when painting portraits. These colors were Vermilion, Burnt Sienna, Yellow Ochre, and Cerulean Blue.¹⁵

A decade later, in 1924, Orpen was still using a limited palette, but it was one that he had expanded somewhat. This new palette, as recorded by Harold Speed in the book The Science and Practice of Painting consisted of ivory black, burnt sienna, raw umber, light red, white, permanent yellow, yellow ochre, deep cadmium, vermilion, cerulean blue, cobalt, viridian, and occasionally, rose madder. (Speed also added that Orpen used copal medium for thinning his colors).¹⁶

As helpful as Fletcher and Speed are in sharing Orpen's color preferences, they unfortunately have little insight to offer into the artist's technique.

The only detailed accounts of Orpen's methods which remain were provided by Sean Keating, a leading painter of portraits and historical subjects in Ireland, and a President of the Royal Hiberian Academy.¹⁷ When Orpen first met Keating, he was a young man of 15 or 16, studying at the Dublin School of Art. He quickly became Orpen's favorite student, and in 1915, when Orpen needed a a new assistant in his London studio, he chose Keating for the job. Though Keating remained always an admirer of Orpen ("My life began on the day he looked over my shoulder in the Life Class," Keating said of Orpen in 1977. "I have loved him all my life. He is in my prayers every night."), he was only a studio assistant for two years. At the outbreak of the first World War, Keating returned to Ireland to avoid being conscripted into British military service, and tried to convince Orpen to do the same, but Orpen instead enlisted, saying, "Everything I have I owe to England."¹⁸ The two remained friends, though not particularly close, for the remainder of Orpen's life.

During an interview with Radio Eireann in 1936, Keating had this to say of Orpen:

What he observed seemed to go in through his eyes, be analysed and arranged by his brain, and written down with inevitable rightness by his unerring hand, as one complicated movement of his will. He painted at an incredible speed without alterations or erasures, and then, if it was not exactly what he wanted, he simply wiped it out and began again – but that was seldom . . . He taught that sufficient paint to create the illusion of light and shade, of tone and colour was enough, and laughed at 'touch,' 'impasto,' 'heureux saleté,' and, to use his own words, 'all that sort of tosh'. He knew how to draw exquisitely with the point, whether with the brush, or a piece of chalk or a lead pencil. And again, to use his own words: 'Either you can draw or you can't, and that's all there is to it.' This mental clarity and hatred of evasion led, as time went on, to the extraordinary breadth, simplicity and conciseness of his later work; the method sinks entirely into the background, and what the picture says is as forcible and laconic, as emphatic and as authoritative, as the shot of a pistol.¹⁹

Then in 1977, in an interview with Orpen biographer, Bruce Arnold, Keating added to his description of Orpen's working habits.

Orpen worked in a temperature of 70˚F, since he suffered greatly from the cold. He painted on 'K' quality canvases, bought from his brother-in-law, Jack Knewstub, at the Chenil Galleries in Chelsea. The canvases were primed with marble dust, and were blue-grey in colour. The texture was very rough. According to Keating it had 'a good bite, a great tooth in it'. He used a priming medium of equal parts linseed oil and good quality turpentine, and gave to his canvas a tint-coating all over of Van Dyke brown, burnt umber or raw umber, or a mixture of these. His palette was limited. Keating remembers a range which included flake white, crimson lake, orange vermilion, chrome yellow, blue, black, veridian (sic) green, raw and burnt umber, burnt sienna.

The advantage of burnt umber, which Orpen generally used for the preliminary outline, was that it dried, in Keating's words 'like the devil', and was very hard to 'move'. Having given the canvas an overall colouring of translucent brown, Orpen's first attack, in monochrome, was 'fundamentally that of a draughtsman. He knew that if the head was right, everything else would follow. And what mattered in the head was that triangle, two eyes and the nose. Never the mouth. The bones under the cheek; they had to be right. Then away he'd go, bringing it all along together, a touch to the eyes, the nose, then back to the face, darting in and out, nimble, alert, always quick and decisive in all his movements.'²⁰

No analysis of Orpen's color choices would be complete, however, without awareness of a mediating factor in Orpen's life – the artist was colorblind. This condition seems not to have been widely known, though comments about his palette were sometimes made ("Mr. Orpen is not thus far a colorist in the full comprehension of the term. His palette has little downright chromatic brilliancy."²¹). It seems his deficiency was not openly acknowledged until the publication in 1927 of the diaries of Orpen's friend, Lord George Riddell:

He (Orpen) says he is a little colour-blind, in as much as he sees red as pink. I think he tries to correct this defect in his pictures – not always with the happiest results. He makes some of his sitters look too rubicund.²²

Apparently, Orpen had protanomaly, or "red weakness," a color deficiency which affects approximately 1% of the male population.²³ To the protanomalous Orpen, any red he saw would have been reduced in value and chroma, and other colors, such as orange, yellow, and yellow-green would have likely appeared to him as shifted slightly in hue towards green. Colors like violet, on the other hand, would have appeared as blue. It is interesting to note that Orpen tried to compensate for the color deficiency as his career progressed, rather than paint in a lower key, as most other colorblind artists would have done; this was quite likely a necessity considering the colorful livery he had to reproduce in his portraits.

In terms of financial gains alone, William Orpen was one of the most successful British portrait artists of the 20th century – if not the most successful – yet he is little known today. He himself predicted, "Twenty years after I die nobody will remember me,"²⁴ which was an unfortunate but prescient prognosis. But why is that the case? For William Orpen, not only was his family responsible for building the myth that shaped the artist, they were also responsible for tearing it down.

In 1952, Sir John Knewstub Maurice Rothenstein, when he published his book Modern English Painters, wrote what was perhaps the most damning criticism of Orpen. Rothenstein, who was Director of the Tate Gallery in London from 1938 to 1964 and therefore a man of importance and influence in the art world, was dismissive of Orpen and his accomplishments. "I have seldom known any man, and never a man of superior talents, with so little intellectual curiosity and so feeble an intellectual grasp, or with so contemptuous an attitude towards the life of the mind as Orpen."²⁵ Rothenstein blamed Orpen's early entry into art training for stunting the artist's mind, and claimed that one of his award winning works from his days at the Slade marked the apex of his career as a painter. The book was well-received and oft-quoted, and did nothing to help Orpen's reputation. And if at times the attacks on Orpen in the book seemed personal, it should come as no surprise then that its author, Rothenstein, was the artist's nephew.

Perhaps it was Karmic. Orpen, with his many public affairs and his issues with alcohol, destroyed his family, particularly his wife Grace (née Knewstub). It was as likely that Rothenstein's opinions reflected his parents' singular feelings for Orpen, as they did the period's fashion of favoring "everything but realism."²⁶ But whatever the motivation, the damage had been done. It has only been in the past few years that Orpen's paintings have begun to regain the prestige they once enjoyed.

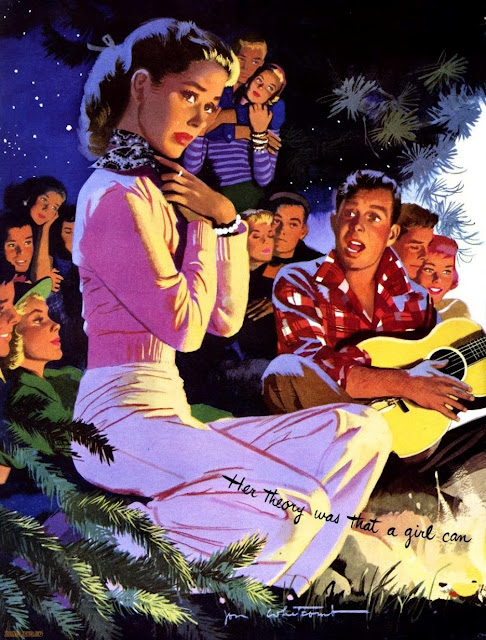

|

| Portrait of Sir William Orpen by one of his Irish studio assistants, James Sleator. |

¹ Konody, P.G. and Sidney Dark, Sir William Orpen: Artist & Man, (Seeley Service & Co., Ltd, London, 1932), p. 27.

² Meynell, Wilfrid, "William Orpen," in The Artist, September, 1901, (Truslove, Hanson, & Comba Ltd., New York), p.177.

³ Konody, p. 209. Konody and Dark list the year in which the painting in question, a portrait of Orpen's patron Charles Wertheimer, was hung in the "gem room" of Burlington House as 1910; In Orpen: Mirror to an Age, author Bruce Arnold, though referencing Konody and Dark, lists the year as 1908. It is possible that the two sources are referring to separate paintings of Wertheimer (there are more than one known), and the story surrounding the honored display may have become inextricably linked to more than one canvas. 1908 was, however, the first year in which an Orpen painting was submitted to and accepted by the Royal Academy.

⁴ Konody, p. 221.

⁵ Upstone, Robert, William Orpen: Politics, Sex, & Death, (Imperial War Museum, Philip Wilson Publishers, London, 2005), p. 28.

⁶ Konody, p. 209.

⁷ Two years Orpen's senior, Eves did not achieve his Associate membership with the Royal Academy until 1933, and his full standing as Royal Academician until 1939. Orpen paid Eves 100 guineas for "laying in a copy" on which he would "then work afterwards."⁸

⁸ Upstone, pp. 28-29.

⁹ Konody, p. 182.

¹⁰ Konody, p. 194.

¹¹ Konody, p. 182.

¹² Konody, p. 222.

¹³ Konody, pp. 222-223.

¹⁴ Konody, p. 193.

¹⁵ Fletcher, Frank Morley, Colour-Control: The Organization and Control of the Artist's Palette, (Faber & Faber Ltd., London, 1936), p. 17.

¹⁶ Speed, Harold, pp. 251-252.

¹⁷ Arnold, Bruce, Orpen: Mirror to an Age, (Jonathan Cape Ltd., London, 1982), p. 170.

¹⁸ Arnold, p. 301.

¹⁹ Arnold, p. 171. Arnold is quoting Sean Keating, "William Orpen: A Tribute," in Ireland Today, vol. 2, 1937.

²⁰ Arnold, pp. 170-171.

²¹ "Exhibition of Paintings by William Orpen," Academy Notes, volume IX January 1914 - October 1914, (Buffalo Fine Arts Academy), p. 134. "Mr. Orpen is not thus far a colorist in the full comprehension of the term. His palette has little downright chromatic brilliancy. He is, rather, a luminist, and light with him becomes a veritable living presence. It is in his manipulation of light that he evinces his incontestable mastery and it is out of light that he evokes his subtlest yet most significant effects."

²² Arnold, p. 369.

²³ "What is Colorblindness and the Different Types?" retrieved July 25, 2013 from [colorvisiontesting.com/color2.htm].

²⁴ Arnold, p. 8.

²⁵ Rothenstein, John, Modern English Painters: Sickert to Smith, (Eyre & Spottiswoode, London, 1952), p. 221.

²⁶ Arnold, p. 404.

2.jpg)