In September 1841, a significant discovery was made when a theretofore missing painting by Thomas Gainsborough was found hanging in the parlor of Mrs. Anne Maginnis, a retired schoolmistress living in England. The picture was a circa 1787 portrait of Georgiana Cavendish (née Spencer), 5th Duchess of Devonshire – a woman "once celebrated as the fairest and wickedest in all of England."¹ It had disappeared around 1792, not long after the Duke of Devonshire had learned that his wife had become pregnant by her lover, Charles Grey, the 2nd Earl Grey, but how Mrs. Maginnis' husband had acquired the portrait remains a mystery. When the painting was rediscovered by the art dealer John Bentley hanging above the elderly owner's mantlepiece (Mrs. Maginnis had actually cut the legs off the portrait so it could fit in that space), Bentley became determined to buy it. Eventually, Mrs. Maginnis acceded, and the portrait passed into Bentley's hands for the price of 56 guineas.

![]() |

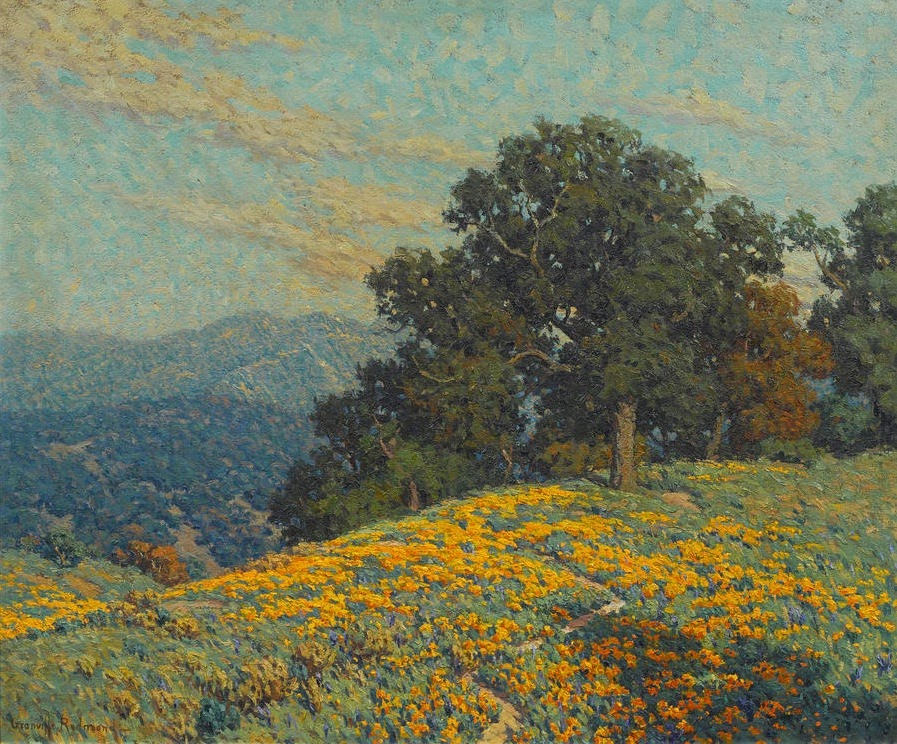

Thomas Gainsborough

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (c. 1787)

oil |

Bentley retained possession of the portrait until the 1860s, when he sold the painting for an undisclosed sum to Wynn Ellis, a silk merchant and Member of Parliament who owned one of the largest art collections in England. When Ellis passed away in 1875, he bequeathed his collection of more than 400 paintings to the National Gallery, which promptly turned about and sold 44 of the best works through the auctioneers Mssrs. Christie, Manson, and Woods of London in May of 1876. Gainsborough's Duchess of Devonshire, was the highlight of the auction, and after some spirited bidding, the portrait went to the art dealer William Agnew for 10,000 guineas – or about $600,000 in today's currency – the most ever paid for the work of a British artist at that time.

![]() |

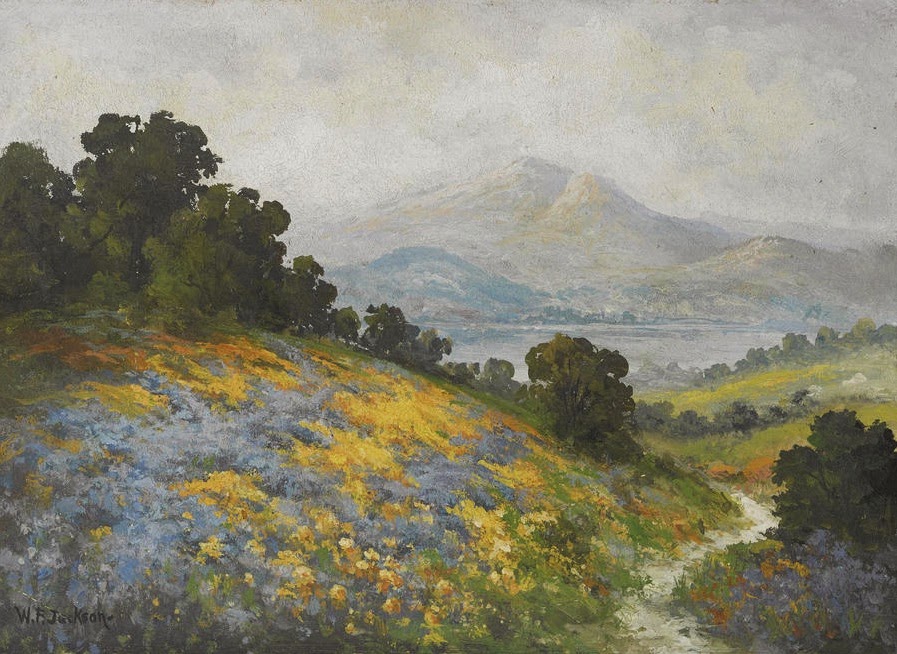

Sir Joshua Reynolds

Study of Georgiana Spencer |

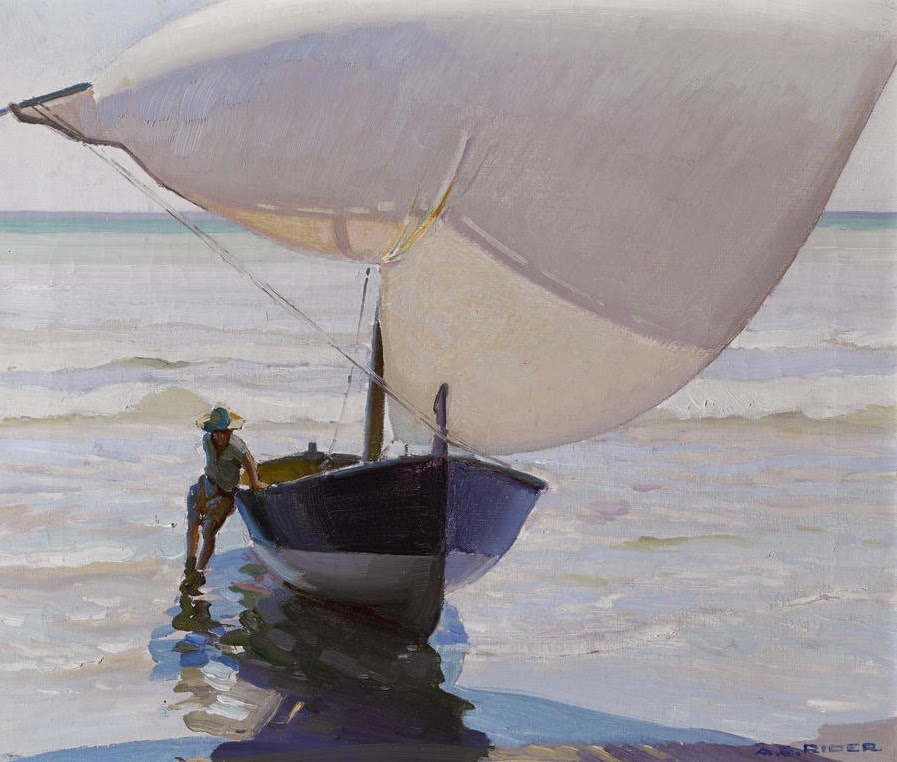

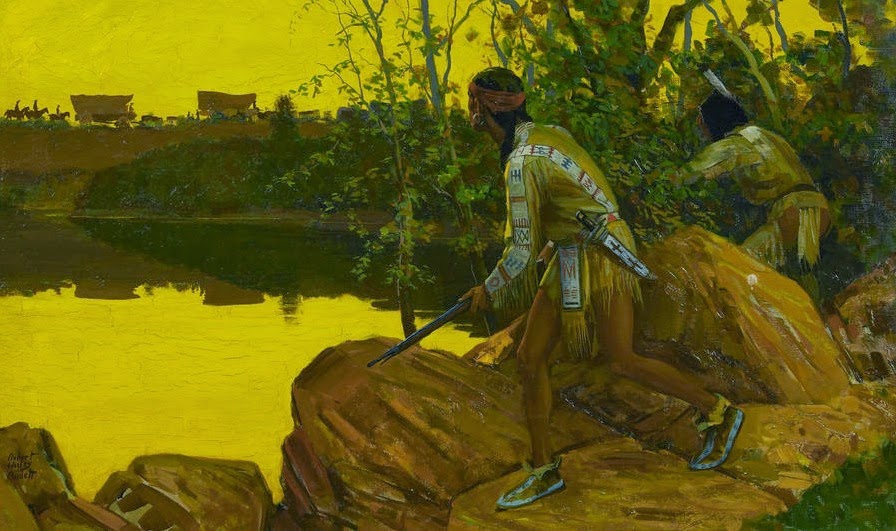

Agnew prominently displayed the painting in his Bond Street gallery, and soon Georgiana-mania took hold of London. Poets wrote odes to the Duchess; her exploits – real or imaginary – began appearing in the social pages; Victorian ladies began emulating her fashions, from powdering the skin and rouging the cheeks and lips, to adopting wide-brimmed and lavishly-plummed bonnets; and members of global high society began arriving in carriages to pay to the Lady their respects. All this attention only added to the painting's cachet, and Agnew was, in short order, able to broker a secret deal to sell the portrait for $50,000 to the American banker and financier Junius Spencer Morgan, who, as a distant relative of Georgiana, coveted the portrait. But before it had passed a month that the Duchess of Devonshire was installed in Agnew's gallery, and before the eager Morgan was able to procure the work, the portrait once again mysteriously disappeared.

![]() |

| Keira Knightley (foreground) as Georgiana Cavendish in The Duchess (Paramount Vantage/Pathé 2008) |

It was to Agnew's great misfortune that at the same moment he was celebrating what should have been a great success, that another man, a clever, master criminal by the name of Adam Worth, found himself in desperate need.

Worth (whose original surname was likely "Werth"), had been born to a poor Jewish family in Germany in 1844, and was raised from the age of five in Cambridge, Massachusetts. At the age of fourteen, hoping to escape his childhood destitution, he he ran away from home, and for the next several years, he bounced around, from city to city, before finally obtaining a respectable position as a clerk in a New York City department store. But perhaps after spending so many years living by his wits, a pedantic lifestyle such as that of a clerk could not hold his interest very long, and after only a month there, the 17 year old lied about his age and enlisted in the Union Army in order to fight in the American Civil War. He rose quickly in the ranks, achieving Sergeant within only two months, but at his first major battle, the Second Battle of Bull Run on August 30th, 1862, he was mortally wounded, and after several weeks of care at a Georgetown hospital, the 18 year old Adam Worth died . . . for the first time.

It is uncertain whether it was the accidental result of the hospital misfiling paperwork or the intentional switching of identities by Worth, but the young and quite-healthy soldier (his injuries at Bull Run were rather minor) saw an advantage to his "death:" he could now re-enlist under a new name, receive a bounty for signing-on, and then desert with the money in his pocket. The plan worked so well, that Worth became a professional bounty jumper, enlisting with and defecting from several regiments, both Union and Confederate. Though this enterprise was not without its dangers, Worth found it to be quite lucrative, and would have likely and happily continued the practice for years, had not the war come to an end, and Worth was forced to seek a new manner of income.

Moving to New York City; a place which attracted criminals of every different social standing, from cutthroats to crooked politicians; the 20 year old Worth fell in with Sophie Lyons, the self-styled Queen of New York's Underworld, who taught the young man to pick pockets. The nimble "Little Adam"– he was only 5'4"– took to his new craft easily, and in short order had had so much success that he was able to finance his own pick-pocketing syndicate. But just as his reputation and his purse were beginning to grow, Worth was caught stealing a package from an Adams Express truck and, late in 1864, was sentenced to three years in New York's infamous Sing Sing Prison.

Nicknamed the "Bastille on the Hudson," Sing Sing was a brutal environment, and Worth vowed to leave it as soon as possible. Putting his naturally keen observation skills to good use, Worth marked the movements of the guards, and after only a few weeks of incarceration, used the moment of a shift change to quietly slip away. Hiding in muddy drainage ditches, stowing aboard a canal boat being ported downriver, and swimming in the cold and polluted waters of the Hudson, Worth made his way back to New York City where his friends clothed him, and absorbed him back into their ranks.

Once again in the Bowery, Worth had the opportunity to reflect upon his life of crime. He had firsthand knowledge that the potential consequences of petty thievery far outweighed the meager rewards it returned. But rather than being swayed from his criminal course, this realization only convinced him that he needed to make the payouts bigger, while shifting the risks to someone other than himself. Using his knack for planning, Worth set himself up as the brain, while his gang became his limbs, carrying out successful crimes throughout the city, from which Worth would take a generous share.

"He ruled the shrewdest criminals and planned deeds for them with craft that bade defiance to the best detective talent in the world." - The Greatest Criminal of the Past Century: Adam Worth

Taking his cues from a new mentor, Fredericka "Marm" Mandelbaum – "the most successful fence in the history of New York"– Worth skillfully moved himself away from lowly street crime, and into the more lucrative world of store and bank robberies. The plans he engineered were ingenious, and above all, safe for all of those involved, and Worth soon became admired by his peers as a master of his craft. But when one of his successful schemes, a nearly one-million dollar theft from a Boston bank, threatened to bring too much scrutiny on "Marm" and her operations, Worth boarded a ship and sailed to England, thereby diverting attention away from friend, while putting himself in a prime location to exert an even greater influence on the world.

"He sits motionless, like a spider in the centre of its web, but that web has a thousand radiations, and he knows well every quiver of each of them. He does little himself. He only plans. But his agents are numerous and splendidly organised. Is there a crime to be done, a paper to be abstracted, we will say, a house to be rifled, a man to be removed - the word is passed to the Professor, the matter is organised and carried out. The agent may be caught. In that case money is found for his bail or his defence. But the central power which uses the agent is never caught - never so much as suspected." -Sir Arthur Conan Doyle The Final Problem

By 1876, Worth had made quite a reputation for himself under the alias of Henry J. Raymond, a name he had borrowed from the founder and editor of The New York Times. With a fortune secretly gained through a criminal network extending from London to Constantinople, onwards to Cape Town, across the sea to Kingston, and back north to Boston, Worth – as Raymond – had become a regular member of high society, with fancy clothes, palatial apartments in Piccadilly, his own racing stables, and a 110-foot steam yacht. And although he had suffered a recent setback when he bankrupted himself to secure the release of members of his syndicate from a Turkish prison, he was on the road to financial recovery when he heard some unwelcome news.

"He never forsook a friend or accomplice."- The Greatest Criminal of the Past Century: Adam Worth

His younger and incompetent brother, John, had been arrested in France trying to pass forged bank notes, and was subsequently extradited to England. This was a maneuver by Scotland Yard designed to punish the older Worth, whom the authorities knew to be a criminal, but against whom they had not been able to bring any charges. Worth wanted his brother released as soon as possible, and had enough money to post the younger man's bond, but according to English law, only a person who owned real estate and had a good reputation could act as a bondsman, and the police were well aware that Worth had neither.

Enter The Duchess of Devonshire.

Worth developed a plan to release his brother that was bold yet simple. He would steal the most famous painting in London and ransom it, not for money, but for the loan of a respectable freeholder. If William Agnew would just put up the bond and vouch for John Worth, the painting would be returned.

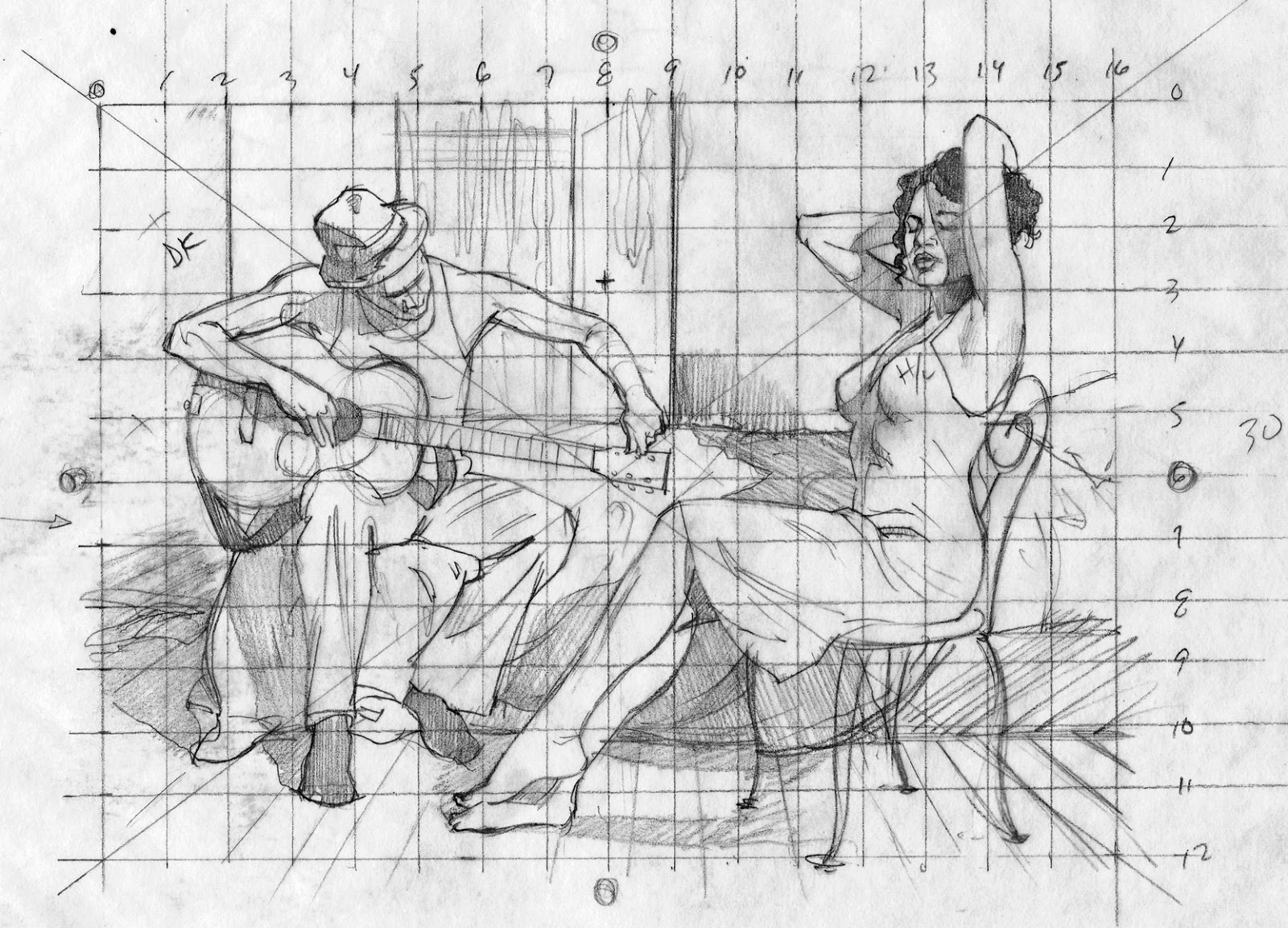

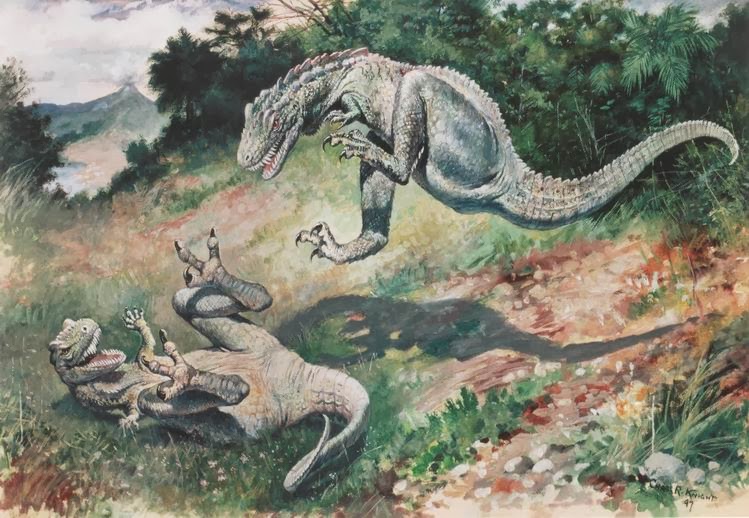

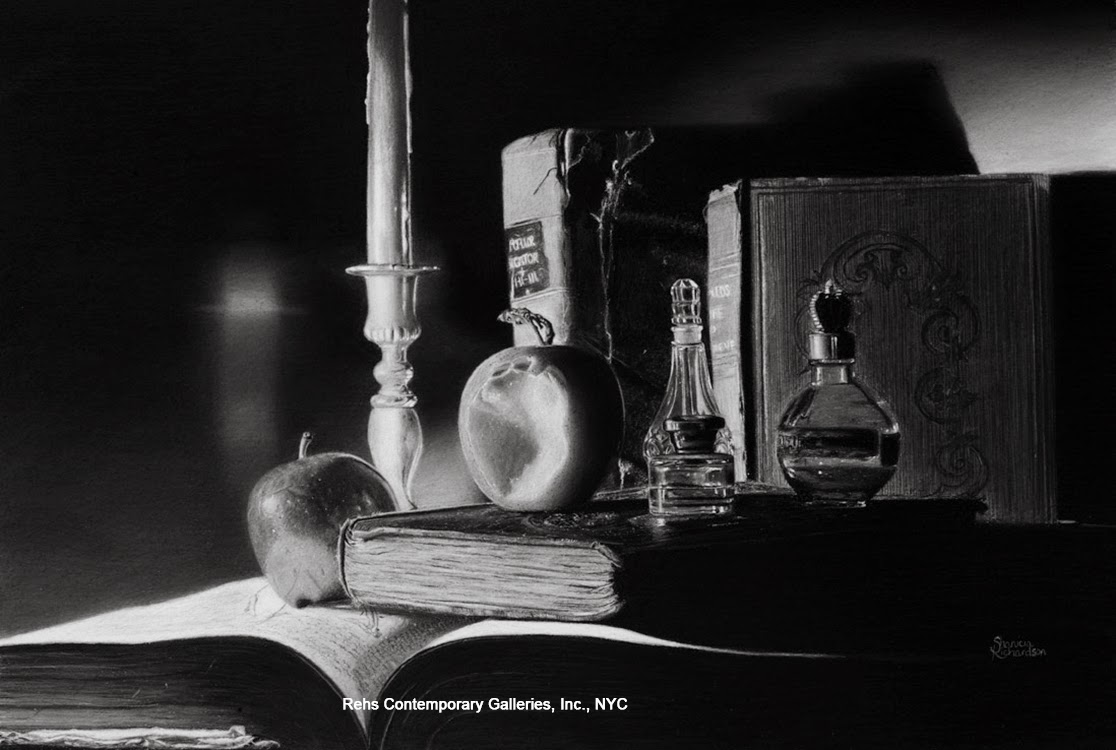

![]() |

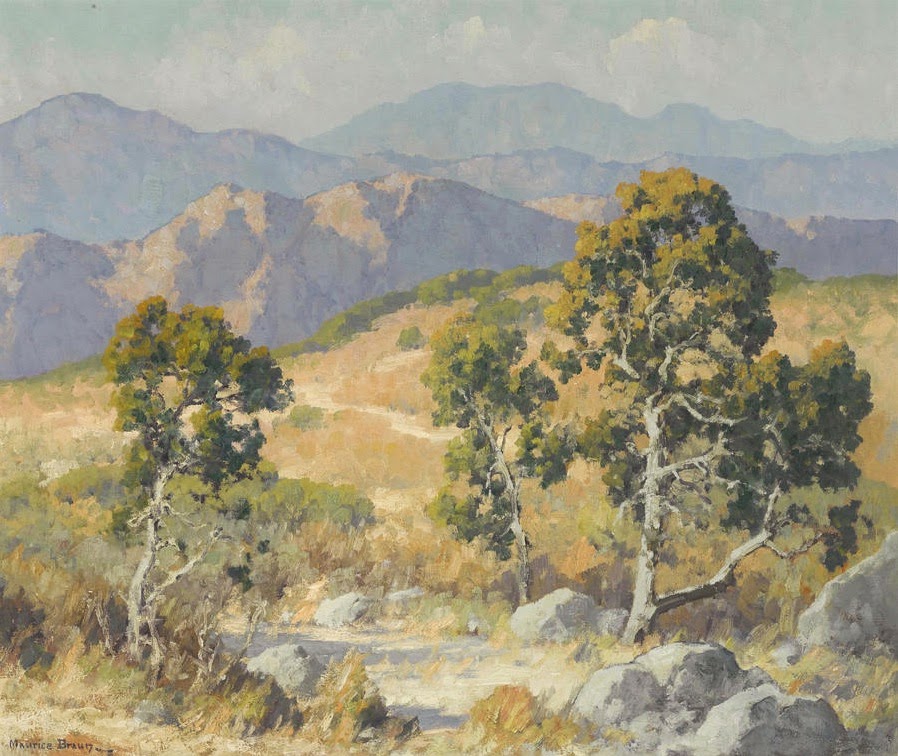

Sir John Bernard Partridge

Au Revoir! (Punch Magazine, February 20, 1907)

15 ⅜ X 11 ¾ in.

pen and ink |

After a simple reconnoitering of the gallery in the guise of Henry Raymond, Worth returned to Bond Street a few nights later with two of his associates. One of the men acted as a lookout, while the other served as a ladder, and within moments, Worth was prying open a second-floor window and heading straight towards the Duchess. As the security guard snoozed on the floor below, Worth carefully cut the painting from its stretcher, moistened its back with paste to make it supple, and, with the image facing outwards so as not to cause cracking, carefully rolled the canvas up. He slipped this tube into his frock coat, climbed back outside the window, and then casually strolled through the fog back to Piccadilly with his two henchmen in tow. In a matter of moments, the most famous painting in England had been stolen.

But before Worth could carry out his plan, he found that he no longer had need of the painting. The lawyers he had hired to represent his brother had succeeded in getting the younger Worth released on a technicality. What then was Worth to do with the Duchess?

He could not sell the painting; it had been famous before the theft, and afterwards, it was infamous. It was a "white elephant," and because of its notoriety, he would never find a buyer for the stolen work.

He could destroy it, and be done with the problem, but surely that would have been a waste, and Worth was not a wasteful man.

Or he could try to ransom the work back to William Agnew, who had already posted a £1000 offer of reward for the painting. This was the course Worth's confederates wanted to take, and so, Worth, through intermediaries, tried to negotiate a price which would ensure the painting's return. £25,000 was demanded for the painting, and though there seemed to be an agreement on the bargain, neither side seemed really committed to the exchange; Agnew, probably because the price was so steep and the likelihood of the painting's actual return seemingly so slim, and Worth for a reason which no one cold have predicted.

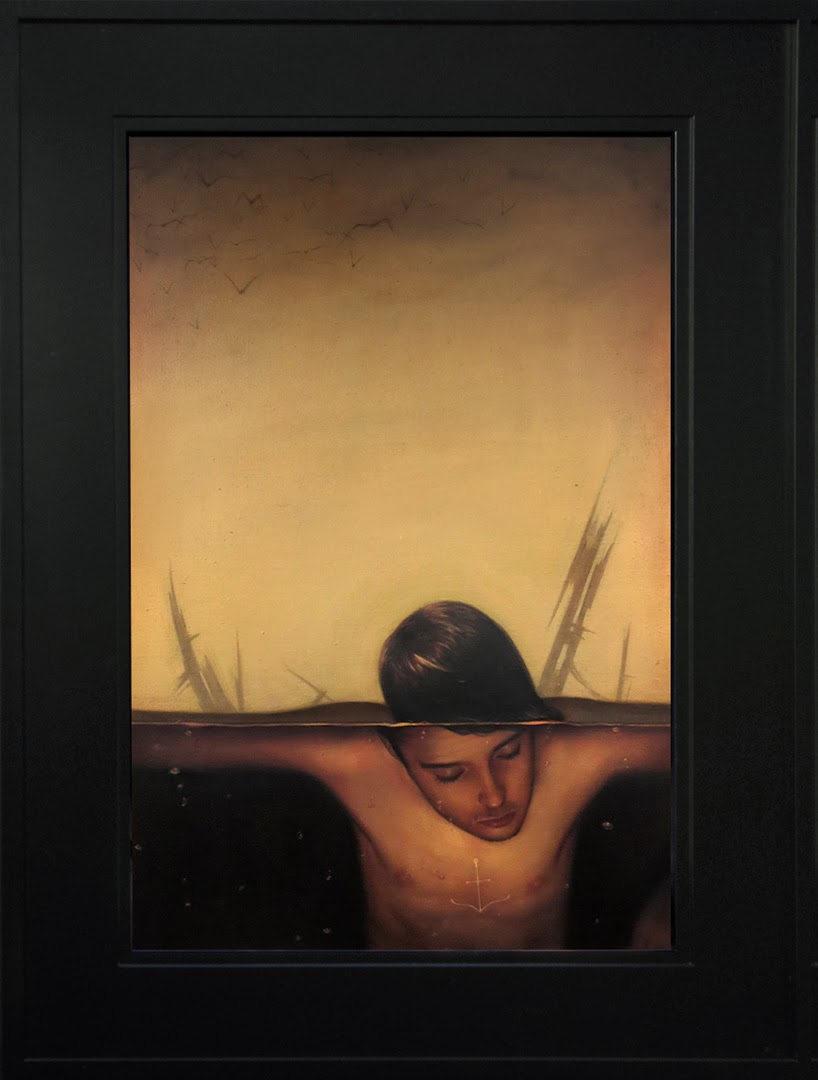

Adam Worth had fallen in love with The Duchess of Devonshire.

For the next quarter of a century, the picture remained with Worth. It traveled everywhere with him, from city to city and across the sea, in a specially-made, false-bottomed steamer trunk. During the night, he would sleep with the painting, sandwiched between two planks and placed under his mattress. He began referring to the

Duchess as his "Nobel Lady," and to his theft of the work as their "elopement," and was known to have purchased gifts for her, including a hunting coat. And during one of his most successful thefts, a $700,000 diamond heist in South Africa, Worth used the painting as inspiration for his disguise, saying he was in the country to purchase ostrich feathers for the women back in Britain who had adopted the fashion of wearing plumed Gainsborough hats. Worth did not separate himself from the painting until he married, at which point he secreted the

Duchess in Philadelphia while he lived with his wife and two children back in England. Every time he visited America, however, he would also visit the

Duchess, moving her to a new location afterwards to ensure her safety.

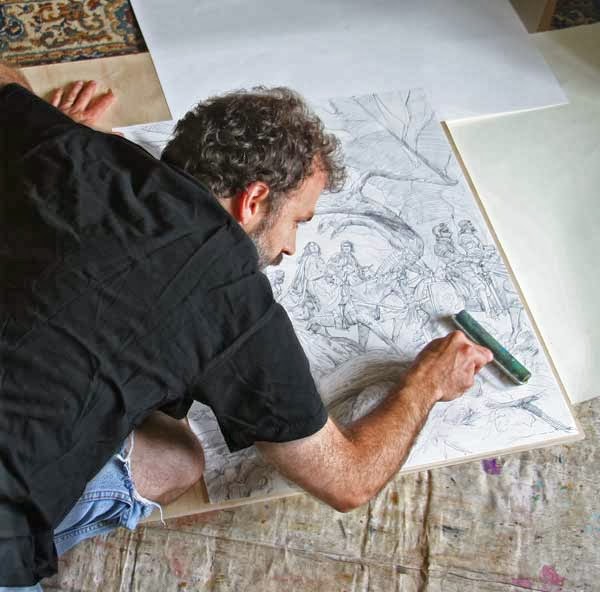

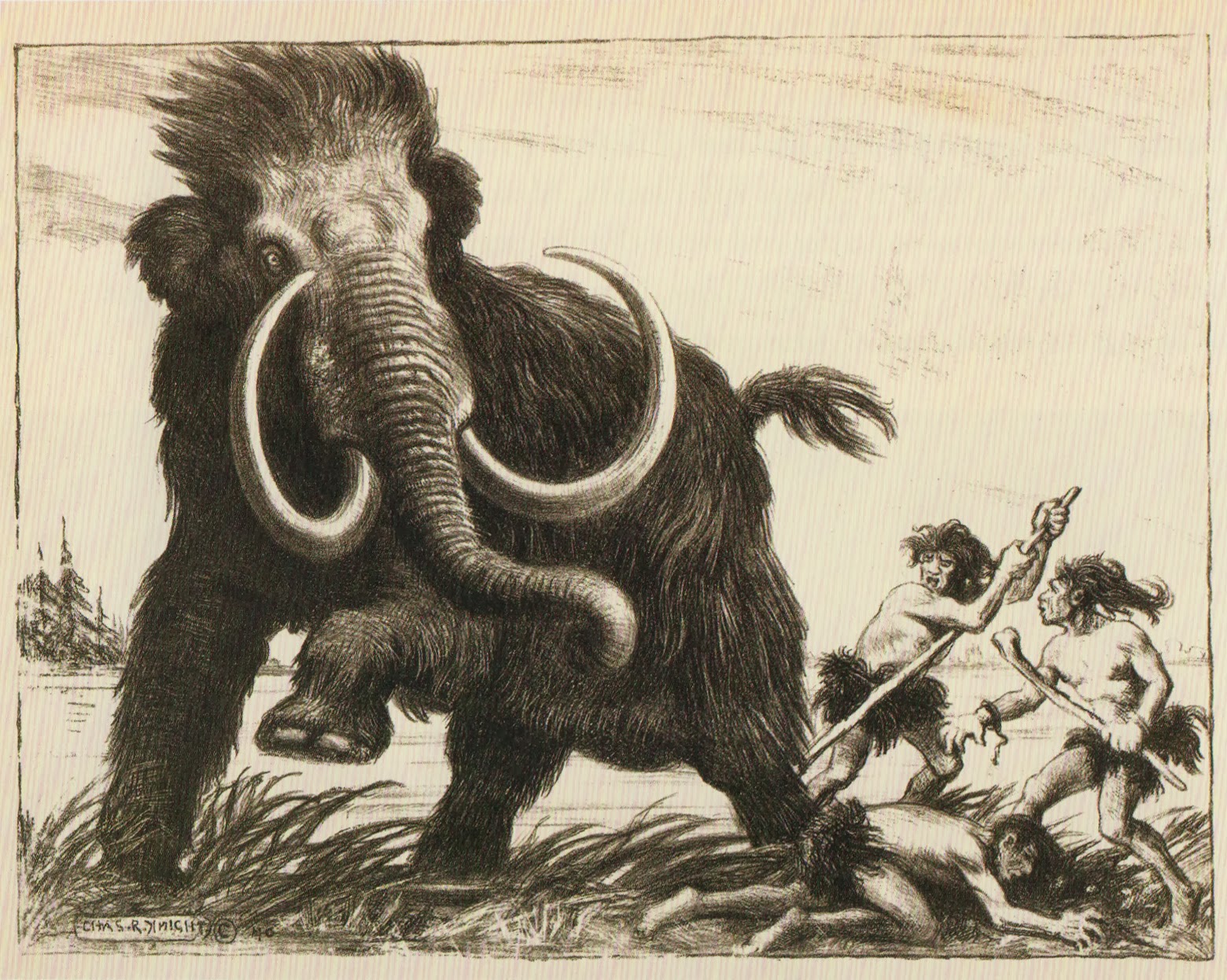

![]() |

Sir Joshua Reynolds

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, with her daughter, Lady Georgiana Cavendish |

In 1892, Worth made a rare mistake, and during a somewhat improvised robbery attempt of a registered mail carriage in Belgium, he was caught. A former accomplice of Worth's who was in prison and felt that he had been snubbed by the man, wrote a letter to the authorities listing every deed the criminal had ever carried off (and some that he had not), thus unmasking Worth. And soon detective agencies from around the world, with the exception of Pinkerton's, started coming forward to verify Worth's true criminal identity. There was no way out, and Worth's empire began to crumble.

He was sentenced to seven years in solitary confinement in Belgium, of which he only served five years. Very shortly into his term, Worth was tricked by a freelance reporter posing as a solicitor into admitting that he was in fact the person who stole the Duchess, and that he was still in possession of the painting. When he learned of his mistake, he recanted his story, but the damage had been done. Several times the Flemish authorities offered him leniency if he would only return the artwork, but Worth refused to admit his knowledge of the Duchess at that point, even to his own lawyer. By the time he left prison in 1897, he was a broken man, ill in health, bankrupt, his wife in a mental institution, and his children being held practically at ransom by his sister-in-law in America. He nothing left, but the Duchess.

In 1899, Worth traveled to America, and agreed to meet with William Pinkerton of the famous Pinkerton's Detective Agency. There was probably no other organization which knew Worth's true exploits better, and, surprisingly, they had developed a certain respect for Worth, not only because of the criminal's prowess, but because he had accomplished all that he had without ever stooping to violence. Worth too respected Pinkerton, feeling he was an honest man, and acknowledging that during his sentencing, the American agency had not come forward to add to the lies (and truths) being presented in court. The two men became, if not unlikely friends, at least unlikely allies. After giving Pinkerton a personal account of the crimes he had committed during his lifetime, Worth told the detective he felt, it was time for the Lady to return home.

Pinkerton made the arrangements, and, having agreed upon a price, C. Morland Agnew, son of the dealer William Agnew, traveled to America in 1901 to retrieve the painting. Worth received $25,000 in the exchange, but he did not part with the work easily. There are rumors that still persist that it was Worth, heavily disguised, who actually handed the Duchess over to Agnew, and that on the journey back to England, Worth, in yet another costume, sailed aboard the same ship.

Worth used the money from the sale of the painting to regain custody of his children, with whom he returned to England. But he never recovered from his time in prison, and died shortly after his return. The children were left with some money from their father, but surprisingly, their income was supplemented by the Pinkerton Agency, which had written an account of Worth's life and donated the proceeds of the book's sale to Worth's son and daughter. Eventually, William Pinkerton even brought Worth's son, Henry Raymond Jr. into the employ of his company.

![]() |

| Irish actor Andrew Scott played Jim Moriarty in 6 episodes of the acclaimed television series Sherlock |

It is likely that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle first became interested in Adam Worth when he read the account written by the freelance writer who had tricked Worth while in prison. Though Professor Moriarty was certainly an amalgam of several figures, Doyle did confess to a friend, Dr. Gray Chandler Briggs, that the real-life criminal mastermind was the primary inspiration for Sherlock Holmes' nemesis.

So even though the real Worth is little remembered today, he is not completely forgotten due to Doyle's efforts.

As for the Duchess, she was purchased from Agnew almost immediately after he announced the recovery of the work by the American J.P. Morgan. "What my father wanted, I want, and I must have the Duchess," declared Morgan. Though the amount paid was not declared at the time, it was later revealed that Morgan had paid $150,000 for the painting. After allowing the masterpiece to go on display for a short period, Morgan installed the work at the family's mansion in Knightsbridge.

In 1913, after the death of Morgan, the Duchess is sent to America, where it was handed down through his heirs until his last surviving grandchild, Mabel S. Ingalls, passed away in 1993. At that point, the family decided to sell the painting, and on July 13, 1994, the Duchess went to auction at Sotheby's London.

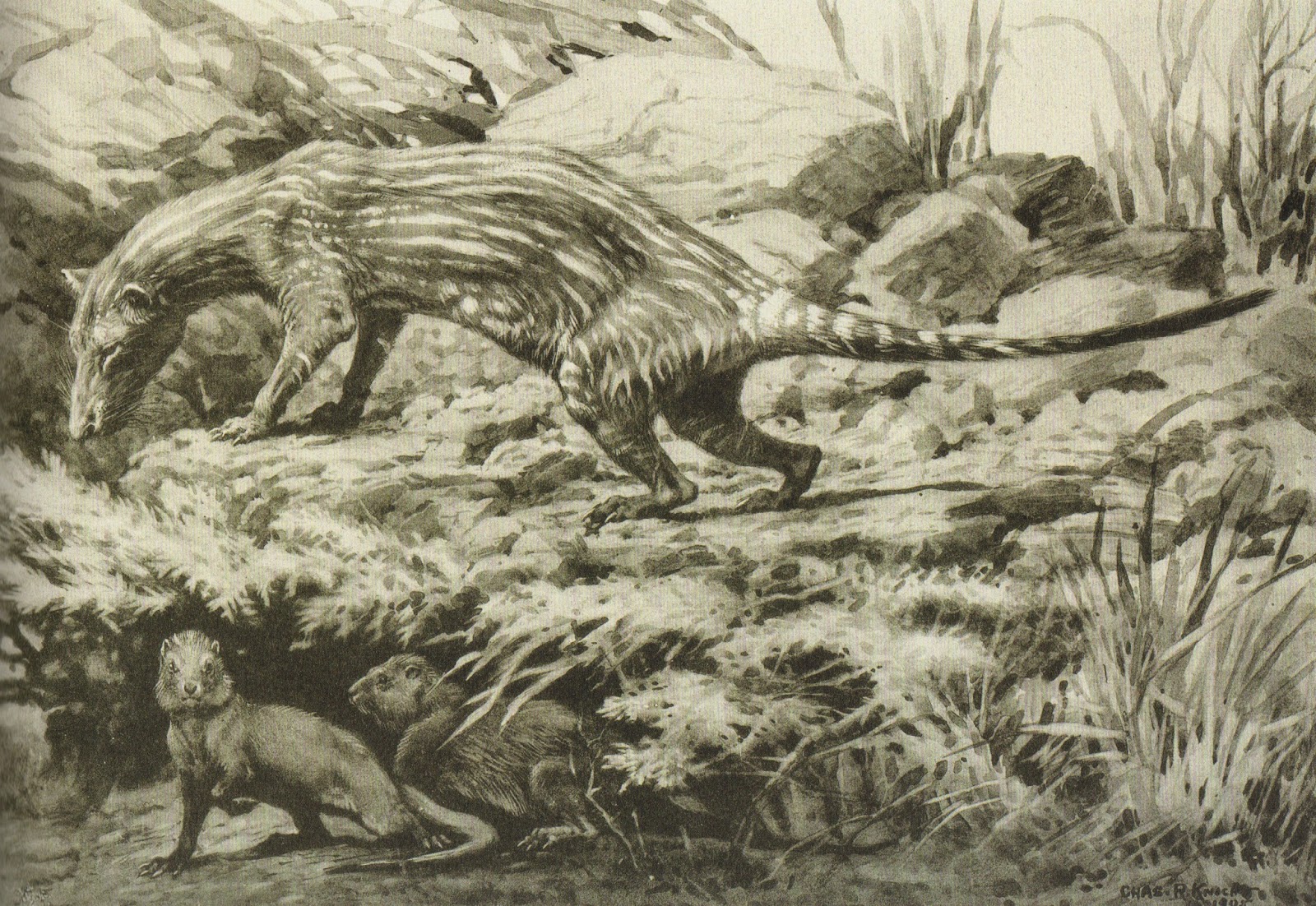

![]() |

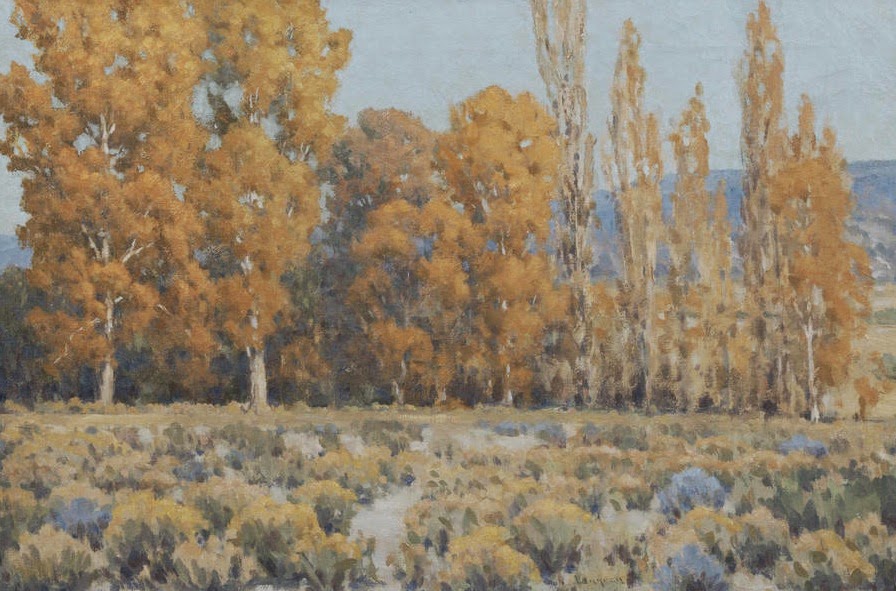

| Chatsworth House |

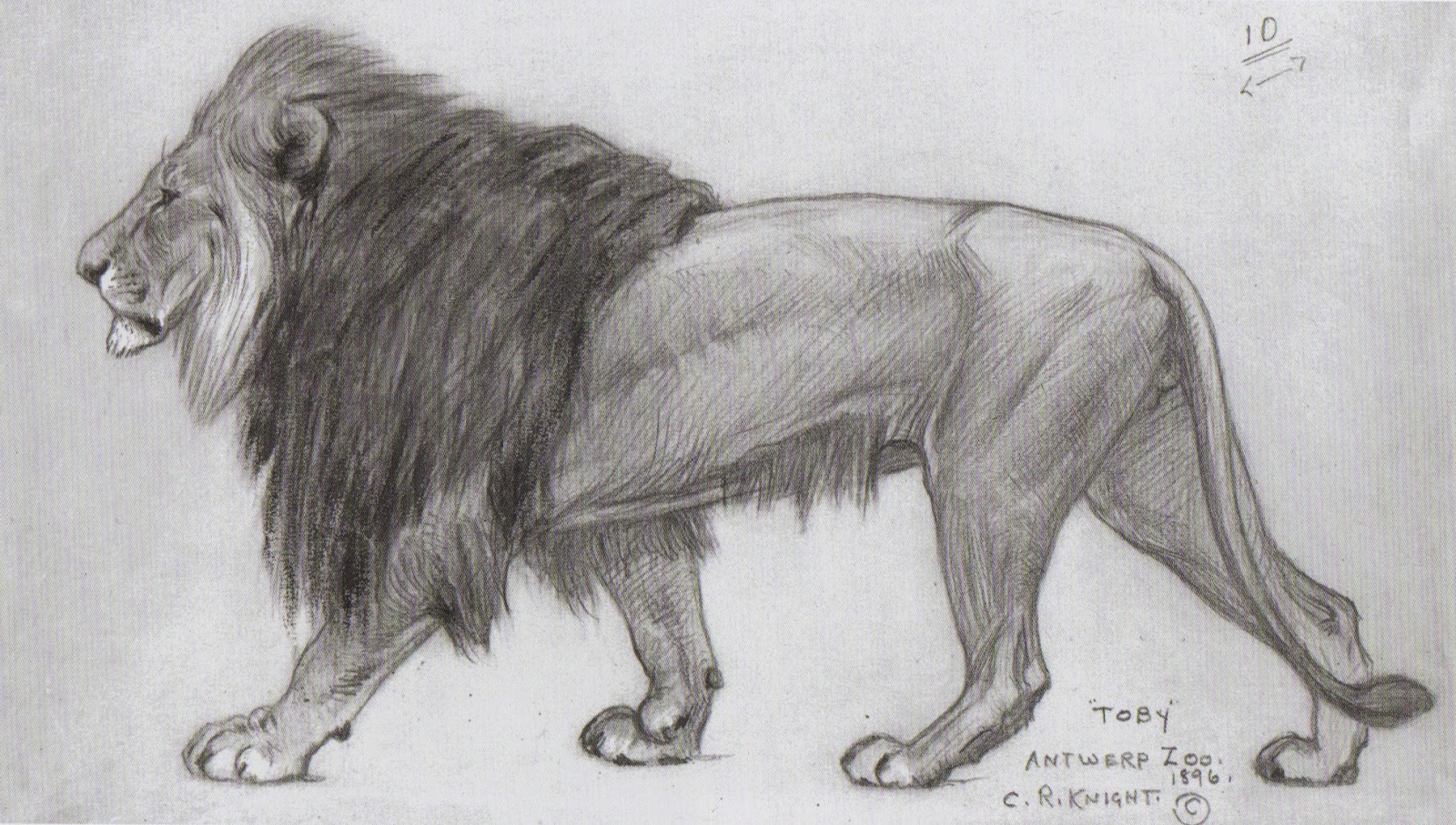

At the behest of the 11th Duke of Devonshire, Thomas Gainsborough's Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire was purchased by the Chatsworth House Trust for $408,870. More than two centuries after its original disappearance, the painting is now finally back with her family, hanging on public display next to a 1787 portrait of Georgiana by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

![]() |

Sir Joshua Reynolds

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire |

¹ Macintyre, Ben,

The Napoleon of Crime: The Life and Times of Adam Worth, Master Criminal, (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, New York, 1997), p. 3.

BibliographyChakraborty, Deblina and Sarah Dowdey, "Who Was the Real Professor Moriarty?" transcript,

Stuff You Missed in History Class Podcast, retrieved January 23, 2014 from [www.hyperlink.com/Adam-Worth-Who-Was-The-Real-Professor-Moriarty-b5AC361B7A4a21].

Doyle, Arthur Conan, "The Adventure of the Final Problem," McClure's Magazine, Volume 2, Number 1, December, 1893.

Geringer, Joseph,

Adam Worth: The World in his Pocket, Crime Library: Criminal Minds & Methods, retrieved January 23, 2014 from [www.trutv.com/library/crime/gangsters_outlaws/cops_others/worth/1.html].

Hinshaw, Victoria, and Kristine Hughes,

Duchess of Devonshire Stolen! Wednesday, May 26, 2010, retrieved January 23, 2014 from [www.onelondonone.blogspot.com/2010/05/duchess-of-devonshire-stolen.html].

Macintyre, Ben,

The Disappearing Duchess, July 31, 1994, "The New York Times," retrieved January 23, 2014 from [www.nytimes.com/1994/07/31/magazine/the-disappearing-duchess.html?src=pm&pagewanted=1].

Macintyre, Ben,

The Napoleon of Crime: The Life and Times of Adam Worth, Master Criminal, (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, New York, 1997).

Pinkerton's National Detective Agency,

The Greatest Criminal of the Past Century - Stole Millions - Imprisoned but Once - Adam Worth, alias "Little Adam:" Theft and Recovery of Gainsborough's "Duchess of Devonshire," New York February 1903, retrieved January 23, 2014 from [archive.org/stream/greatestcrimina00agengoog#page/n5/mode/2up].

.jpg)

.jpg)